Author – Schenelle Dlima // Editor – Erin Pallott

“My voice did not obey me. I tried to answer, but could only indicate yes or no.”

“I had fantasies and was horrified: the nurses were dangerous. I was attending my own funeral.”

“I have been from Heaven to Hell.”

No, these are not lines from an indie psychological thriller. These are first-hand accounts of patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) who experienced delirium. Delirium is a clinical condition characterised by sudden changes in a person’s attention, awareness, and cognition. These changes develop over a short period (hours or days), and the severity fluctuates over time.

For the etymology aficionados out there, the term delirium has its roots in the Latin phrase deliro-delirare, meaning ‘to go out of the furrow’, or to deviate from a straight line, to be deranged, to be out of one’s wits. This tells you a lot about the psychological state of someone with delirium. We may have thrown around the phrase “you’re being delirious!” at some point in our lives (I’m also guilty of this!). However, in the medical world, the word delirium holds more weight, with potential long-lasting effects on the individual.

What happens in delirium?

Delirium can manifest in several ways in people. Broadly, delirium’s clinical features can be bucketed under impairment of consciousness, thinking, memory, psychomotor behaviour, perception, and emotion. People with delirium find it difficult to focus and stay attentive, to tell the time and date, to remember facts and people, and to process things happening around them.

There are three types of delirium:

- Hyperactive delirium (also called excited delirium): Patients appear more agitated and aggressive. They may also experience mood swings, delusions, hallucinations, and poor sleep.

- Hypoactive delirium: They are less active than usual, speak slower, and speak much less, and are drowsier. Patients appear more withdrawn and are less aware of what’s happening around them.

- Mixed delirium: Patients fluctuate between manifestations of hyperactive and hypoactive delirium.

Who’s vulnerable to delirium?

Delirium can happen to anyone, but there are certain characteristics and circumstances that can greatly increase the chances of experiencing delirium. Multiple risk factors contribute to delirium development and progression. A review by Wilson and colleagues (2020) neatly categorises these risk factors as follows:

- Predisposing risk factors: These relate to the characteristics of the patients. Older age, dementia, frailty, high number of chronic conditions, depression, and visual and hearing impairment can raise the risk of delirium. For example, people with dementia have a 2–4 times higher risk of developing delirium.

- Precipitating risk factors: These risk factors are related to acute illnesses, injuries (fractures or head injury), or drug use (medication withdrawal or changes). Acute illnesses can include urinary tract infections, sepsis, stroke, or liver failure among others.

Hospital admission for planned surgeries and emergencies can increase the risk of developing delirium. After a surgical procedure or staying in the ICU, healthcare staff and loved ones sometimes notice behavioural and cognitive changes in the patients, suggesting the onset of delirium. This had implications during the COVID-19 pandemic — evidence suggests that 20–30% patients hospitalised with COVID-19 develop delirium, and 1 in 2 patients in the ICU may develop delirium.

How is delirium diagnosed?

Delirium can develop in many patients in hospital settings, but the condition is challenging to detect and diagnose in a timely manner as it can manifest so variably. This is especially true for hypoactive delirium, as it’s often mistaken for fatigue or depression. Observations by loved ones and caregivers can be helpful in detecting delirium, as they’re in the best position to notice even minor changes. For example, comments like “they are sleeping more than usual” or “I’m worried they are depressed; they just stay in their room all day” can signal delirium.

How can healthcare staff suspect a patient has delirium? First, they perform a bedside clinical assessment to determine the patient’s attention and arousal levels, presence of cognitive deficits, and presence of other mental status abnormalities. Second, insights on short-term changes from baseline levels are sought from the patient, caregivers, and healthcare staff familiar with the patient’s history and medical records.

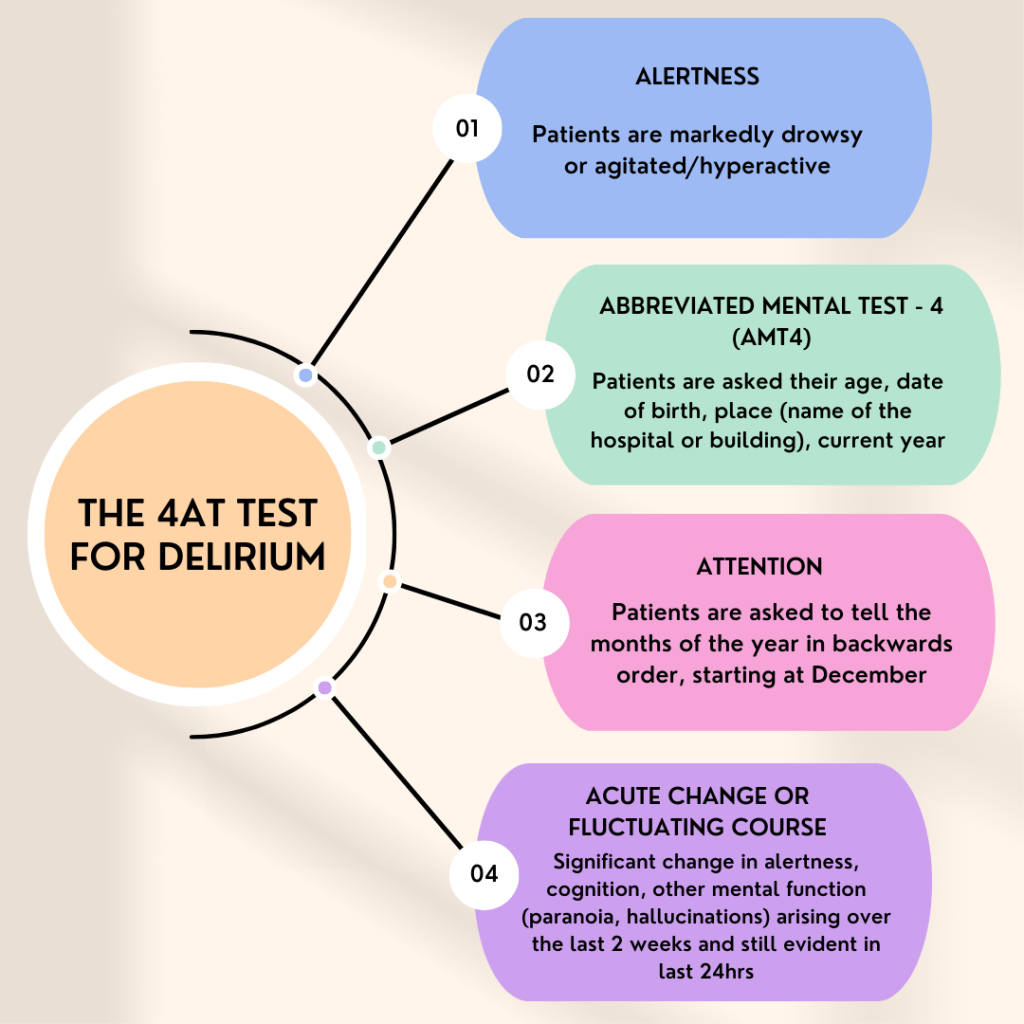

If healthcare staff suspect delirium, several tools exist to detect and diagnose delirium in clinical settings. Two common ones are the Confusion Assessment Method and 4AT clinical test. The figure below demonstrates how delirium is detected using the 4AT clinical test, which was developed in Scotland.

How is delirium treated?

Managing delirium is challenging as multiple factors contribute to the condition. Delirium management generally includes four key steps: addressing the triggers of delirium episodes, controlling behaviour changes, preventing complications linked with delirium, and supporting the patient’s functional needs.

In the UK’s NICE guidelines, the initial management for people diagnosed with delirium involves addressing the underlying causes, effectively communicating with the person, reorienting them, and reassuring them. In persons with delirium who are distressed or considered a risk to themselves or others, verbal and non-verbal de-escalation techniques are recommended. If these don’t work, healthcare staff can consider medications.

In summary, there’s no one-size-fits-all approach to manage delirium — factors like the patient’s age, the presence of underlying chronic conditions, and whether the person received surgery or spent time in the ICU are important to consider.

Why does delirium deserve our attention?

Delirium is common in hospitals after a surgical procedure or stay in the ICU, but how common the condition is in community settings is poorly understood. In hospitalised older adults in general medical settings, a pooled analysis found that delirium occurred in 23% of these patients. The type of surgery (minor or major) also influences the risk of delirium onset. Evidence also suggests that at least 1 in 5 high-risk patients undergoing major surgery, especially in emergency settings, develop delirium.

The words “sudden”, “short-term”, and “acute” are generally used to describe the course of delirium, but the impacts are anything but temporary. Delirium can adversely affect the patient, their loved ones, and the healthcare system.

For patients, delirium can increase the risk of early death, dementia onset, loss of functional ability to carry out daily tasks, and admission to care homes. Around 7–10% of patients with delirium after surgery die within 30 days of the surgical procedure. In a study conducted among around 12,000 older adults in Scotland, 31% of people who were diagnosed with a delirium episode developed dementia within 5 years. These research studies emphasise the short- and long-term impacts of delirium episodes on patients.

For loved ones, witnessing delirium episodes can be greatly distressing. Coping with their loved one being hospitalised is difficult enough, but the onset of delirium after surgery or being in the ICU can be a source of confusion, anxiety, and apprehension for family members and friends. In some cases, delirium can last for months, and people may never revert to their old selves. This can bring additional burden to the family members and caregivers, long after discharge from the hospital.

From a health system perspective, patients with delirium stay in the hospital for longer, bringing about higher healthcare costs. Research shows that older hospitalised patients with delirium have significantly higher medical costs than those without delirium. In a study conducted in the USA, estimated healthcare costs related to delirium after major surgery were USD $32.9 billion each year. Another report from Australia found that delirium was directly responsible for AUD $4.2 billion (around GBP 2.3 billion) in healthcare expenditure per year.

What delirium research is going on in the University of Manchester?

In the UK, delirium is being increasingly recognised as a serious clinical condition in older adults that warrants more attention. The University of Manchester is engaging in delirium research that aims to benefit clinicians, persons with delirium, and their caregivers. Here’s a snapshot of what’s in the pipeline:

- The NIHR Applied Research Collaboration Greater Manchester (ARC-GM) Healthy Ageing Theme and the University of Edinburgh are working on pooling evidence on the link between delirium and falls in the community. Falls are major problems among older adults in the community as they’re associated with fractures, hospitalisation, permanent loss of mobility, and high healthcare costs.

- A team from the University of Manchester and Dementia United have published details of the implementation of a community delirium toolkit that was developed and piloted during the COVID-19 pandemic. The toolkit aimed to help safely care for people with delirium at home. A qualitative evaluation was completed by a team in the ARC-GM Healthy Ageing Theme and is being submitted for publication.

- Facilitated by a Dementia United programme, delirium information leaflets are being translated into multiple languages so that they’re easily accessible to different communities residing in Manchester.

- Delirium prevention content is also being added in the KOKU digital health intervention, a gamified digital strength and balance programme for older adults developed with the support of the University of Manchester.

Special thanks to Professor Emma Vardy, Consultant Geriatrician at Salford Royal Hospital, for her review and insights.

Discover more from Research Hive

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.