Author: Agnes Chan // Editor: Erin Pallott

I believe most of you have seen that in movies life-threatening events are often depicted in slow motion. Have you ever wondered that it may be true that time is slowed down during certain events? There are several situations in which time was reported to have slowed down or things appeared to happen in slow motion. For example, people often report time slowing down during car crashes or other high-adrenaline situations. These situations are often associated with high levels of fear and danger. If time appeared to be slowing down, it implies that the speed of the internal clock increased during the event. Similar phenomena were reported in military firefights and professional players of high-speed sports reporting their opponents moving in slow motion. It can also be seen in more ordinary events like anxiously waiting for a doctor’s appointment and the passing of time felt slower. These examples all suggest that the internal clock speed may be related to the rate of processing of information around us. Studying these events brought the potential relationship between time perception and information processing speed under the spotlight.

How We Experience Time and Keep Track of It

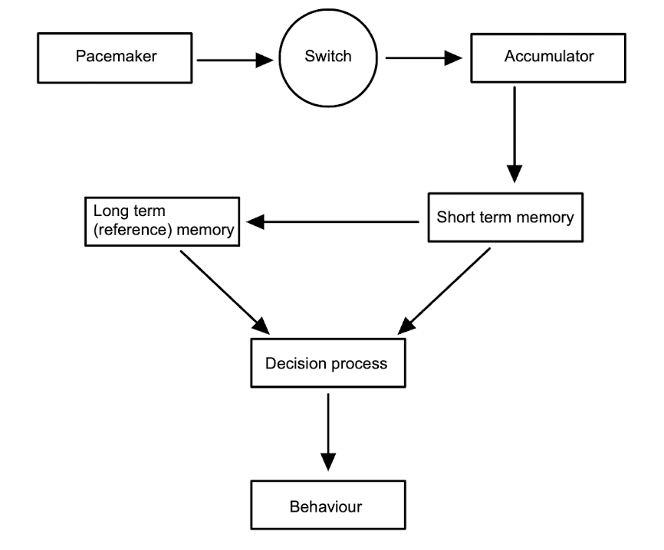

The idea that time perception in humans is controlled by an internal clock can be traced back to the early 1900s. The theory behind the internal clock, namely scalar expectance (or scalar timing) theory (SET) was first studied in animals. SET is then applied to humans to investigate the properties of the internal clock. The diagram below shows a version of SET focussing on information processing.

The internal clock consists of a pacemaker and an accumulator that are responsible for timing events. In the SET model, other than the internal clock, working memory (or short-term memory) and long-term memory are also involved. The pacemaker and accumulator are connected to each other by a switch.

- Pacemaker: responsible for producing pulses

- Accumulator: responsible for storing the pulses.

When a stimulus or an event that needs to be timed starts, the switch closes and allows the pulses to flow from the pacemaker to the accumulator. When the timing event ends, the switch opens and terminates the transfer of pulses between the two parts. The accumulated pulses are then transferred to working memory. If there is a discrimination between a standard duration and a stimuli duration, the memory for the standard duration will be transferred to the long-term memory as a reference while the memory for stimuli duration remains in the working memory. In human timing experiments, the reference memory is established through a number of standard trials. To generate a decision, the durations in the working memory and the reference memory are compared.

There are two types of decision-making, temporal generalisation and temporal bisection.

- Temporal generalisation: to decide whether the just-presented duration is the same as the standard duration that was presented previously.

- Temporal bisection: to compare the just-presented duration and two durations that were presented previously (long and short). Participants are asked to decide which one the just-present duration is closer to, hence generating a behaviour.

Factors influencing the internal clock

The internal clock speed can be influenced by various factors:

- Body temperature

- Dopaminergic drugs

- Modality of the stimulus

- Boredom or low arousal

- Repetitive stimulation such as:

- Visual: a series of flashes

- Auditory: click trains

Through arousal manipulations

Arousal here refers to how strong the emotion one is experiencing. For example, people are highly aroused in life-threatening situations as they experience strong feelings of fear and anxiety. On the other hand, when people are bored, they are less aroused since they are not experiencing strong feelings or emotions. It is proposed that repetitive audible clicks can increase arousal and hence increase the rate of the pacemaker. An increased rate of pacemaker generates more pulses and hence increases subjective time. Studies have also suggested that reduced arousal leads to slowing down of the subjective time. However, emotional manipulations are hard to carry out in the laboratory due to ethical concerns.

Through frequency manipulations

It is suggested that everyone’s internal clock has a particular frequency. If the frequency of the click trains presented matches the internal clock frequency, it would strengthen the pulses generated by the pacemaker and hence influencing the rate of the internal clock.

Through entrainment

Entrainment is another proposed theory behind the effect of click trains where the frequencies in the brain that are similar or equal to the frequency of the repetitive stimulation of flickers, would increase in amplitude. This results in sympathetic entrainment in the neurons firing to the repetitive stimulation of flickers. Although this effect has only been demonstrated in repetitive stimulation of flickers, it may be applicable to click trains due to their mutual repetitive nature that the amplified frequencies in the brain may increase the speed of the internal clock.

Effect of repetitive stimulation on the speed of the internal clock

A study discovered that when the stimuli and trains of repetitive clicking sounds or visual flickers were presented together, the perceived duration of the stimuli was longer than when the stimuli were presented without clicks or flickers accompanied. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that trains of repetitive clicks and flickers didn’t need to be presented alongside the stimuli to generate the effect. They could be presented before the stimuli and the same results were obtained. Participants were asked to judge the duration of the stimulus presented, in either visual or auditory form, by estimating them in milliseconds, the estimated duration of the stimulus would be longer than the actual duration when the stimulus was presented after click trains. The effect demonstrated by click trains on the internal clock is multiplicative meaning that the overestimation of the duration is positively correlated to the duration of the stimulus or event that needs to be timed.

Slope effect

The slope effect refers to a difference in slope between the click and no-click conditions. It provides evidence that the internal clock is sped up when clicks are presented. A study demonstrated the slope effect through repetitive stimulation. The slopes for the estimated stimuli duration preceded by clicks or flickers were significantly greater than that preceded by silence showing that the relative overestimation of the duration that needed to be timed increases with the actual duration. The slope effect was significant for both auditory and visual repetitive stimulation. This further showed that presenting a train of clicks would increase the speed of subjective duration by increasing the speed of the pacemaker. In addition, the effect is only observed when a train of clicks or flickers is presented. White noise and silence have no effect on changing the speed of the internal clock.

Effect of repetitive stimulation on the speed of information processing

Click trains are also found to increase the rate of information processing. A research group conducted experiments on the effect of click trains from three perspectives: reaction times, time for information processing and the amount of information that can be processed. They recorded the reaction times on a 1-, 2-, or 4-choice reaction task with either clicks or white noise beforehand and compared them to those with a silent condition. This experiment aimed to find out whether clicks would lead to a faster reaction or not. The results revealed that when a train of periodic clicks is presented before the onset of stimuli, the reaction time was shorter than when no clicks are presented. The same influence of click trains is also found in the reaction times for solving arithmetic problems. Participants were presented with a mathematical addition problem and a potential answer preceded by either clicks, white noise or silence. They had to react to the question as fast as possible on whether the answer was correct or not. The reaction times for trials preceded by clicks were found to be shorter than those preceded by white noise and silence. These two experiments demonstrated that the faster the internal clock, the faster the reaction time.

The study also used two memory tasks to find out whether people can process more information in a display when it is preceded by clicks. They discovered that participants could remember and recall more letters correctly when a click train was presented before the stimuli were presented. However, the error rate also increased with the number of letters recalled correctly in clicks condition suggesting that people could be producing more letters regardless of whether they are correct or incorrect. In addition, the iconic masking task also revealed more pictures were recognised when the presentation was preceded by a click train than silence showing further evidence that more information can be processed when the rate of the internal clock is increased. In a nutshell, click trains not only increase the speed of the internal clock but also the rate of information processing on tasks that do not involve time judgements. This study proposed a potential link between the internal clock and information processing.

Overall

Over decades of conducting research on the effect of repetitive stimulation on the speed of the internal clock, it has been discovered that presenting repetitive stimuli would increase the speed of the internal clock and hence reduce the reaction time. Although the link between the internal clock and information processing has not been proven, studies have proposed a potential correlation between the two. Further investigation is needed to unveil this mystery so that we can better understand how humans perceive time and information and how it can be influenced.

Discover more from Research Hive

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

61 thoughts on “Life in Slow Motion: Can Time Perception and the Speed of Information Processing be Manipulated?”