Author: Nina Wycech // Editor: Erin Pallott

The time has come for me to start my Master’s project in Bioinformatics, and to do so, I need a big dataset ready to analyse. But how do I get it in time, and most importantly, without collecting it myself in the clinic? Thankfully, there is a shared scientific database that people like me can use – UK Biobank. It comprises information that is supposed to reflect the UK population that can be accessed by scientists, thus enabling them to draw bolder conclusions. The larger the sample they study, the higher the confidence in the results they have. However, the more I spoke about it to my friends and family, the more I realised how unknown it was. So here I am, asking – what do you know about UK Biobank?

UK Biobank Data

Data available in UK Biobank is, importantly, secure and de-identified, meaning that it takes precautions for it to 1) not be accessed without permission, and 2) not provide any information that could allow for the identification of a participant.

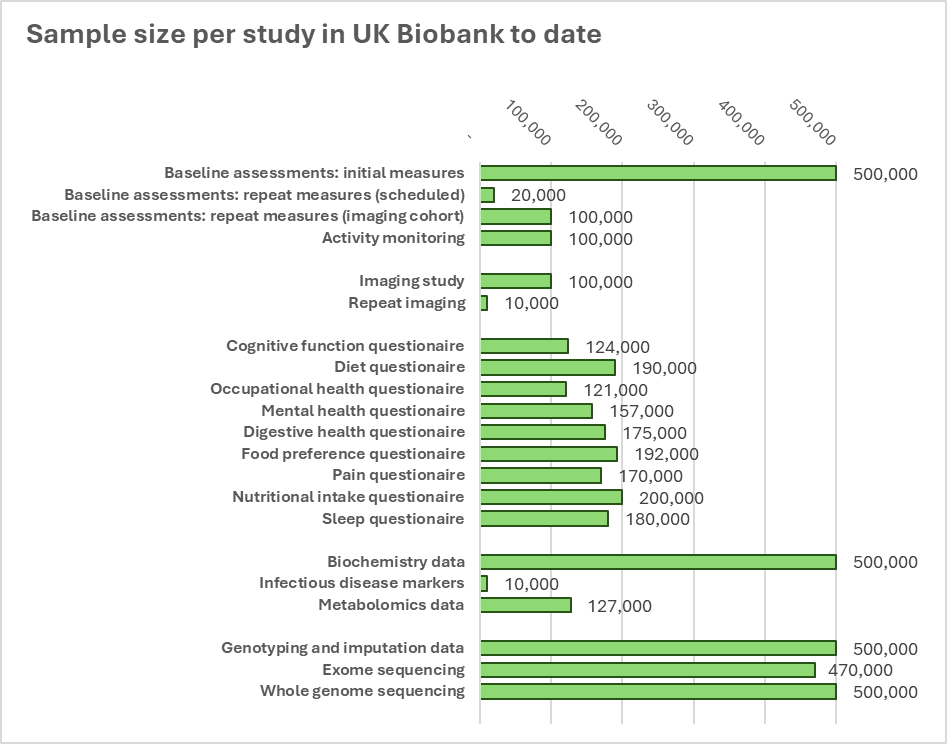

The initial dataset was collected from 500,000 people between the ages of 40-69, recruited across the UK (England, Scotland & Wales) between 2006-2010. During their initial interviews, they donated biological samples (blood, urine, and saliva), described their diet, and had their bone density, breathing, and muscle function checked.

Since then, the database has grown exponentially larger. To investigate the changes in time, 20,000 people from the initial group were invited to take repeat measurements. Every fifth of the initial cohort also had their physical activity measured for a week, and every tenth, their heart, brain, and abdomen imaged, participating in the largest imaging project in the world. Moreover, the advances of scientific tools enabled the creation of genomics, proteomics, and metabolomics libraries. Additional context is provided by the past and ongoing questionnaires and activity measurements. The newest update released in March this year shared more brain scans and insight from the sleep questionnaire. The multi-modality of data collection brings one closer to the complete picture of one’s health – for example, linking their genetics, nutrition, and mental and physical health.

For the Good of Mankind

It wasn’t until 2012 – two years past the data collection stage – that the data became accessible. Not everyone is permitted into the UK Biobank, however. It accepts applications from all researchers who have public health in mind, whether they work academically, commercially, governmentally, or charitably. Up until this year, the site has also considered applications from insurance companies. They do not have to work in the UK – in fact, 80% of access applications come from abroad. Before being accepted, applicants are verified. They have to be employed by a legitimate research organisation (including students) and share their research history. Relevant in this day and age, they also can’t be under any international sanctions. Finally, everyone has to pass e-learning courses on confidentiality to ensure that they are educated about fair usage of sensitive data, especially on the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Is There a Catch?

Firstly, access to the database is not free, nor is analysing it on their Research Analysis Platform. The pricing varies, being more expensive for advanced datasets (such as genomes). It is considerably cheaper for students and researchers from low- or middle-income countries. Moreover, as the goal of the platform is to advance public knowledge. Researchers are expected to share their results with the scientific community upon finishing their project.

To Be Continued

The UK Biobank project is far from complete. It is currently building its new headquarters just next door to The University of Manchester. Their funding is also secured until 2028, comprising mostly of charitable donations, philanthropic donations (eg from former Google CEO Eric Schmidt), and governmental support via UKRI.

What’s to come? The data will continue to be updated, with further baseline measurements, imaging, and biochemical assays. One of the aims is to monitor the SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in 20,000 participants over time. Other goals include finding disease biomarkers in an expanded proteome database.

The future of the UK Biobank is inextricably linked to the researchers who analyse the database, looking for patterns within it and sharing their findings. Hence, even without expanding the source data, there is still much more to be learned with every starting hypothesis.

Bio: Nina Wycech

Pronouns: she/her

I consider myself a collector of fun facts and interesting stories – which often come from science. I’m somewhat of a scientist myself. I graduated B.Sc. Neuroscience from UoM and I’m currently continuing my education at Glasgow doing an M.Sc. in Bioinformatics. My favourite subject is sleep & circadian rhythms, but I’ve been exploring genome sequencing extensively throughout my study.

Discover more from Research Hive

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.