Author: Osman Khaleel // Editor: Cherene de Bruyn

Cover image from Pexels

*Archaeology: The study of past human cultures through the material culture (artefacts) left behind.

*Lithics: Archaeological artefacts made from stone, including hand axes, scrapers, projectile points and knives.

*Cataracts: Areas on the Nile between Aswan and Khartoum where the water is shallow.

BACKGROUND

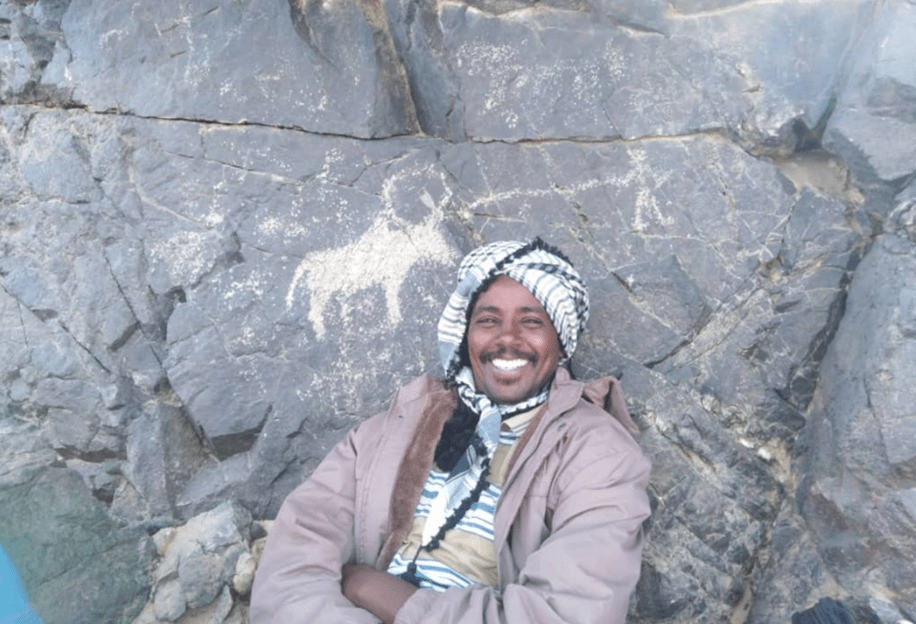

Growing up in Sudan, surrounded by beautiful landscapes and various stories from my grandfather about the past, an early fascination with the human past and its mysteries became part of my life. This irrepressible passion led me to study archaeology at one of the oldest archaeological departments in Sudan (Department of Archaeology, University of Khartoum). Archaeology, as a discipline and field of study, is only really well known to educated and professional individuals in Sudan. As a student in the early 2000s, I quickly realised that the job market for archaeology is extremely limited, with few opportunities for sustainable employment or career growth. As a result, after graduating in 2007, I took a long break from academia and started my own business while pursuing my passion for archaeology as a freelance archaeologist for almost a decade. September 2016 was a turning point in my life. I had the opportunity to join Prof. Claudia Näser of the University College London, Institute of Archaeology, United Kingdom, on archaeological excavations in the Fourth Cataract Region. This opportunity marked my first international collaboration. As part of her team, she offered me opportunities to join the 14th International Conference for Nubian Studies, in Paris 2018, and to also attend a one-month training in the Aurignacian site of Breitenbach in Germany. Since then, I felt this field has become more of a lifestyle to me than a hobby or a specialisation. As such, I decided to move forward and do my MA in this amazing field, as I was determined to contribute to communicating this subject among students and the local community, aiming to preserve the rich cultural heritage of areas that I used to work in or visit.

Within this narrative, my MA has been done as part of a Sudanese project “El-Ga`ab depression archaeological project an ancient Paleolake in the western desert of northwestern Sudan” directed by Prof. Yahia Tahir of University of Khartoum. I was quite lucky as soon as I defended my Master thesis in February 2020; I had the opportunity to join the newly established Department of Archaeology in Sudan (Department of Archaeology and Folklore, University of Gadarif, Sudan) as a lecturer. In this position, I could work with the same devotion and conduct more fieldwork in archaeology, focusing on the archaeology of desert or desert-like landscapes, surrounded by the pure beauty of nature and the quiet stillness that shapes a pure mind.

THE PRESENT

Starting a PhD is often described as a journey of intellectual discovery, where the student develops their perseverance and creates positive change. For me, seeking a PhD abroad is one of my dreams since it can provide me with in-depth training and an opportunity to develop my skills. This dream is a forward step and has been closely linked with my personal and professional growth, characterised by exceptional challenges and rewarding milestones.

October 2022 was another turning point in my academic pathway when I joined The Interdisciplinary Center for Archaeology and the Evolution of Human Behaviour (ICArEHB), in a fully funded PhD position part of DISAPORA project directed by my supervisor Prof. Nuno Bicho, of the University of Algarve, funded by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia (FCT), Portugal. The project is titled “The first human migrations in the Nile Valley: The Kerma region during the Middle Stone Age” and includes collaboration with Dr. Sol Sánchez-Dehesa Galán (ICArEHB and the Dpto. de Prehistoria, Historia Antigua y Arqueología, Facultad de Geografía e Historia, Universidad de Salamanca, Spain) as a co-supervisor.

My research focuses on the study of palaeogeography – the study of how landscapes such as rivers, deserts and coastlines have changed over time – with a particular focus on the Nile and surrounding deserts. I examine patterns of land use and cultural diversity through a combined analysis of multidisciplinary approaches, such as techno-typological studies of stone tools (lithics) in conjunction with GIS (Geographic Information Systems) modelling, to better understand the human past.

As it is well-known to every postgraduate student, every PhD journey has its own tests and hurdles. Some are, however, more challenging than others. The ongoing war, as of April 15th, 2023, in Sudan has made my academic journey even more complex. Nonetheless, this experience has consolidated my dedication to pursue African archaeology, regardless of the political situation. Many African countries face similar problems regarding the protection of both tangible and intangible cultural heritage. In my homeland, Sudan, archaeological heritage and efforts toward protection and conservation are no different. From the moment I began my academic career, I was drawn to prehistoric archaeology, particularly the lifeways of early human adaptations. In this sense, the Middle Stone Age (MSA) in Sudan represents a critical period of technological and behavioural development that has its own significant implications for understanding the origins and dispersal of modern humans within and out of Africa. My study area — the Kerma region of northern Sudan — with its special landscape and endless tributaries of watercourses, holds great potential to shed light on the adaptations of early humans to changing environments during the last 200,000 years. In my project, I will reconstruct the past landscape by looking at the lithic (stone tool) assemblages from this region. Through this analysis, it will be possible to understand the regional movements, cultural interactions, resource use and technological change among the MSA peoples who lived in this region.

The presence of various MSA stone tools, including stone tools of the Nubian Levallois method (stone tool type linked to the dispersal of early human out of Africa during the MSA) found in this region, make it possible to understand early mobility cultural trajectories and adaptations in the Kerma region and the Nile Valley in general.

Nubian Levallois core from the The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

CHALLENGES AND ADAPTATIONS

Due to the data inaccessibility caused by the ongoing war in Sudan, instead of relying on primary field data (the physical lithic tools) housed at the Sudanese National Corporation for Antiquities Museums (NCAM) in Khartoum, I must search for an alternative way and different methods to overcome this complicated situation. GIS-based, remote sensing analysis was the first option in my mind since the coordinates were already collected as part of our last season, 2023. Archival lithic collections (Sudanese Pleistocene data, some of which has been housed in European institutions and museums in Belgium and France, for several decades) will form the technological base analysis for my research in order to reconstruct the Pleistocene landscapes of Sudan. This shift required extensive training in spatial archaeology and digital mapping techniques, skills that were not originally part of my academic background. To fill this gap, I sought out opportunities for specialised training by applying for funding to attend GIS workshops and courses at institutions such as the MAPPA Lab in Pisa, Italy, or Wrocław University in Poland. Several proposals for funding have been submitted, and I am waiting to hear about the outcome.

While this transition was challenging and time-consuming, it was also a valuable turning point and a great learning experience, without which the proposed new analytical tools and methods wouldn’t be part of my research. It also taught me an important lesson: adaptability is the key to success in the academic world. A PhD is not only about answering research questions and defending your dissertation, but also about developing yourself to overcome unexpected obstacles.

Aside from overcoming logistical challenges, my PhD journey is also a time of great intellectual growth. Working in an interdisciplinary peaceful research environment at the ICArEHB keeps introducing me to different perspectives and has given me the opportunity to study different courses in the first year of my PhD, as well as allowing me to interact with scholars from different fields. These scientific interactions have broadened my understanding of human-environment dynamics and encouraged me to integrate multiple lines of evidence into my future research.

Despite the high pressure and worries about the country, my family and beloved ones, during this complicated situation for more than two years, one of the most rewarding aspects of my PhD has been the opportunity to contribute to theoretical discussions of human adaptation in the Sudanese landscapes. By creating a synthesis and a database for the MSA in Sudan which presents a unique future case study to examine how early humans survived within different fluctuated, environments, and climatic zones, and how did they adapt to resource scarcity, and developed their different technological strategies for survival within the frame of Sudanese landscapes during the Pleistocene. By synthesising archaeological and environmental data, I am trying to provide a holistic account of human resilience and innovation in the region.

THE FUTURE: BEYOND THE PHD

Accomplishing my PhD despite the setbacks and change of approach will be a stepping stone, contributing significantly to the conservation and heritage management of Sudanese Pleistocene archaeology. Additionally, volunteering my database to the NCAM will provide a solid foundation for heritage management in Sudan after the war. 3D modelled lithic artefacts, housed in European institutions, will form the initial contribution for the proposed virtual museum. This suggestion was proposed by NCAM after the loss of most of the museum`s collection. As part of my PhD, I also want to improve intellectual relations between Sudanese researchers and other organisations and promote international cooperation. I strongly believe that in this way we can develop sustainable research methods that will improve the knowledge of Africa’s prehistoric past and at the same time enable local scholars and communities to actively participate in the preservation of cultural heritage.

In conclusion, some of the most important lessons I have learned so far are:

- Unexpected challenges will arise from nowhere in no time; you should always be ready, since the ability to pivot and find alternative solutions is what makes a successful researcher.

- Working with international scientists from different scientific backgrounds (at ICArEHB) has broadened my perspective and improved the quality of my work.

- Conferences, workshops and joint projects provide important platforms for knowledge exchange and professional growth.

- Taking part in diverse training events and workshops hosted by different schools and departments added more value to my critical thinking skills, as well as my ability to interpret findings for the different archaeological sites and periods.

- In addition to academic publications, our work should contribute to site management, heritage conservation and capacity building in the regions we study, especially those which are under special political circumstances, after the situation becomes better.

Finally, I would like to thank the staff of University of Khartoum, and Prof. Claudia Näser and her team for teaching me the first steps in the field of archaeology. FCT Portugal and DIASPORA project of the University of the Algarve for their tireless support and generous funding of my doctoral thesis. There are no words sufficient to express the warm hospitality and unwavering support of the ICArEHB community, which has truly become a second family to me during this difficult period of my life. Special thanks go to my two supervisors, Prof. Nuno Bich and Dr. Sol Sánchez-Dehesa, without whose support this trip would not have been possible, and finally many thanks to the University of Gadarif in Sudan for their kind support. Please do not forget to pray for Sudan.

About the Author

Osman Khaleel is currently a PhD candidate at the Interdisciplinary Center for Archaeology and the Evolution of Human Behaviour, Universidade do Algarve, Portugal. His research focuses on the interdisciplinary study of human evolution and prehistoric archaeology. In addition to his doctoral studies, he holds a teaching position in the Department of Archaeology and Folklore at the University of Gadarif in Sudan. Mr Khaleel’s academic interests lie at the intersection of archaeological fieldwork, cultural heritage and evolutionary anthropology. He is committed to advancing the scientific understanding of early human behaviour in both research and teaching. Feel free to reach out at: Osmankhalil2@gmail.com / okkarrar@ualg.pt

Discover more from Research Hive

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Navigating the PhD journey amid prolonged conflict: Challenges, growth, and resilience”