Author: Dalia Aziz // Editor: Nithya Eswaran

You have likely come across the term “endocrine disruptor”, particularly on social media, which got me wondering – what is an endocrine disruptor? How do they work, and are they truly as harmful as people say?

According to the Endocrine Society, there are nearly 85,000 synthetic chemicals in the world, and it’s possible that 1,000 or more could be endocrine disruptors. Now, I couldn’t possibly fit all that into a few pages. However, I will focus on one of the major endocrine disruptors, which are parabens. Parabens are endocrine active chemicals that are found in pharmaceuticals, food, and cosmetic products. Most consumers recognise that parabens are something to avoid and would choose a paraben-free alternative, but many aren’t exactly sure what parabens are or why they are used in the first place.

With that in mind, I want to offer a quick disclaimer before diving into the main article. My intention here isn’t to present an exhaustive list of harmful products and tips on how to avoid exposure, as there’s plenty of information readily available online. Instead, I’m more interested in asking the deeper questions: why and how? This piece focuses on how parabens actually work and why they’ve been linked to disease, drawing on the research I’ve been exploring. If you’re someone who enjoys learning about the science behind the headlines, this one’s for you.

What are parabens and why are they used?

Parabens are preservative agents that are added to products to prevent the growth of yeast, mould and bacteria. They are ideal for manufacturers as they are incredibly stable, inert, colourless, odourless, tasteless, insoluble in water, and low-cost. They’re found in a wide range of personal care products from moisturisers and haircare to make-up and shaving creams.

Parabens have long been regarded as highly effective preservatives across multiple industries, leading to widespread use since the 1920s. By 1995, their prevalence was evident, with studies reporting their presence in 77% of rinse-off and 99% of leave-on cosmetics. It was not until the early 21st century that there was an emergence of research regarding the potential adverse health effects that parabens may be causing. Since then, there has been a dramatic shift in manufacturing, marketing and legislation to restrict the use of parabens, especially in personal care products. This is due to the fact that although parabens can be inhaled and ingested, it is widely recognised that the primary route of exposure is through dermal absorption.

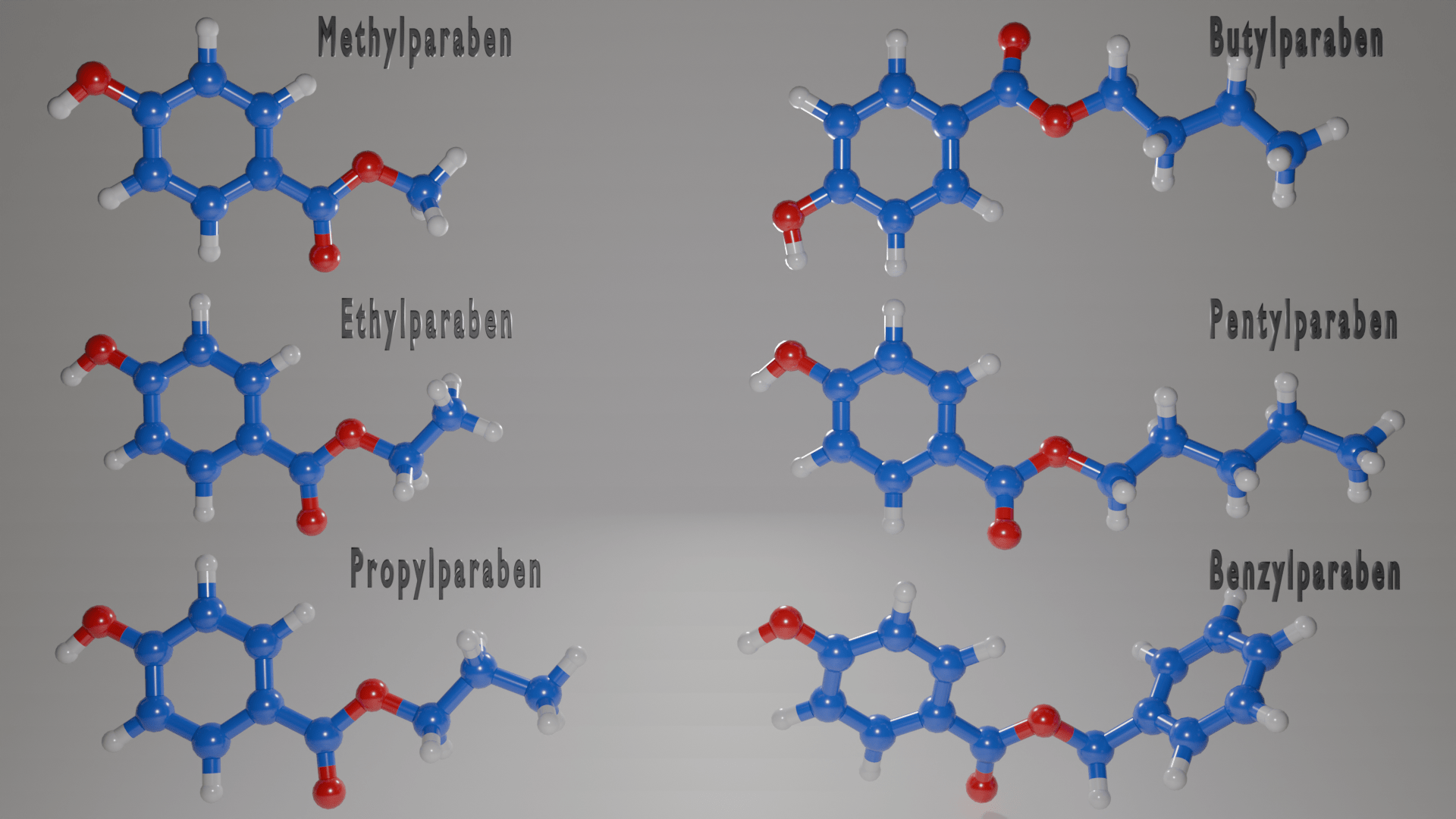

What do parabens look like?

Before we get into the research, I think it’s important to understand the structure of these chemicals as it relates to their function.

Now wait!

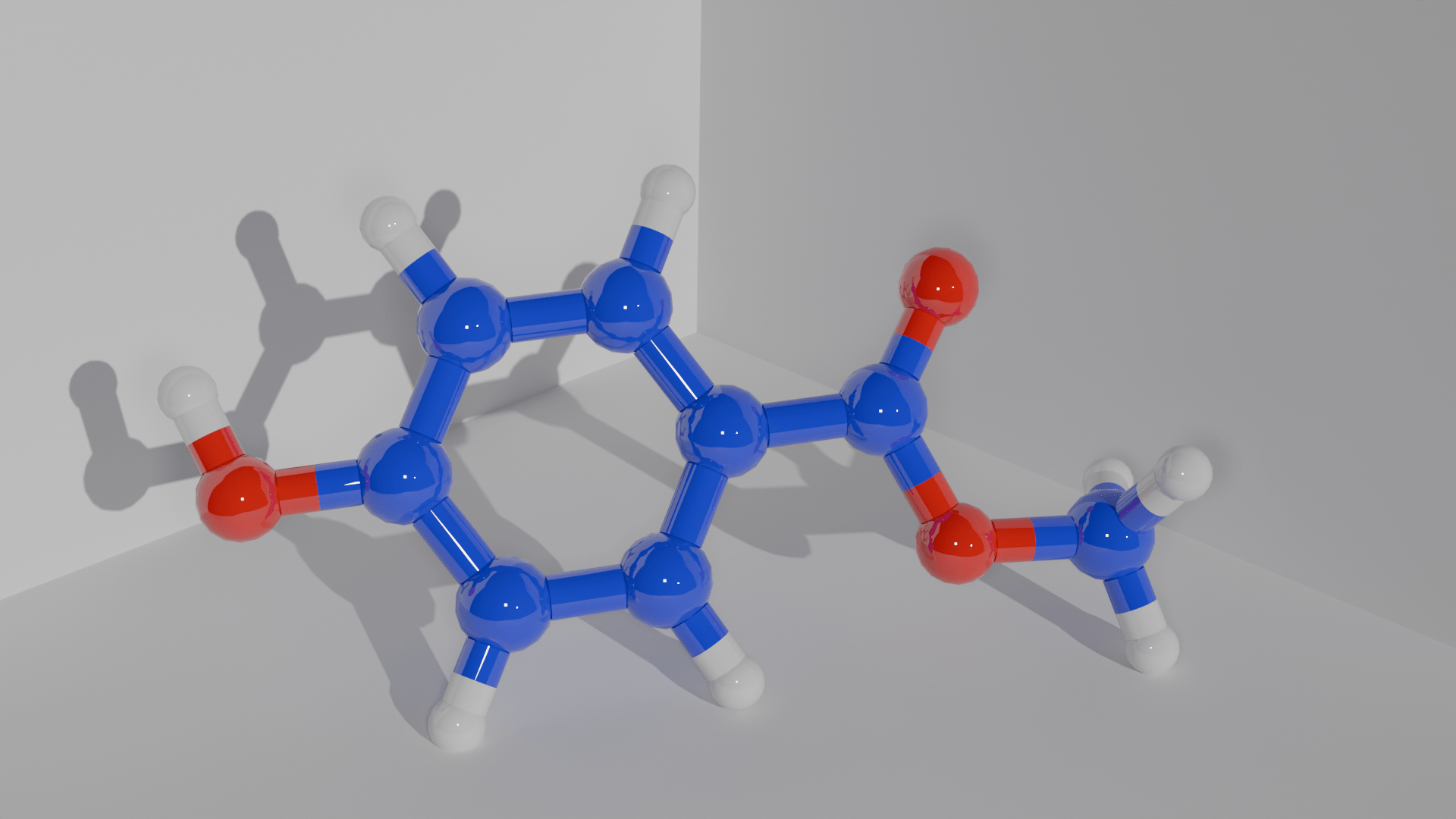

Before you lose interest – I will keep it short and simple. Chemically, parabens are alkyl esters of 4-hydroxybenzoic acid. I can hear your sighs from beyond the screen. All you need to know is that parabens contain a hexagon ring structure termed a phenol ring, which is connected to an alkyl chain through an ester group. The nomenclature ‘methyl, ethyl, propyl…’ refers to how many of these alkyl groups are chained together. In the diagram provided, I have only gone up to 5 alkyl groups for simplicity, but there are a variety of lengths and structures out there.

The structure of parabens is incredibly relevant, as there is a direct relationship between the length of the alkyl chain and the preservative nature of the paraben. For example, butylparaben has a 4 times greater efficiency to inhibit microbial growth than methylparaben. Unfortunately… the longer that alkyl chain… the more endocrine disruption. Parabens are regulated based on the length of their alkyl chain, so it’s important to understand the different types.

What kind of parabens are allowed in our products?

Let’s be clear, parabens are not banned chemicals and are still being used in a variety of products. However, not all parabens are used to the same extent. Typically, the most prominent parabens used for cosmetic purposes include methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben, and butylparaben, but longer chain parabens can still be used depending on regional and product regulations.

For example, The Official Journal of the European Union stated that the European Commission allows for a maximum concentration of 0.4% or 4g/kg for a single paraben ester and 0.8% or 8g/kg for mixtures of all parabens in cosmetics within EU countries. The EU has permitted smaller chain parabens such as methylparaben and ethylparaben as they are considered safe at these concentrations, but propylparaben and butylparaben have a reduced concentration of 1.9g/kg of product. In 2014, they banned isopropylparaben, isobutylparaben, phenylparaben, benzylparaben and pentylparaben due to their higher associated risk of harm.

However, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has a more relaxed approach, as according to themselves, cosmetic products and ingredients do not need approval before they are sold on the market as they are not colour additives. As of February 2022, the FDA has stated that they “do not have information showing that parabens as they are used in cosmetics have an effect on human health” and that “to take action against a cosmetic for safety reasons, [they] must have reliable scientific information showing that the product is harmful when consumers use it”. The uncertainty surrounding the use of parabens impacts the regulatory bodies that govern public safety, which puts the responsibility on the consumer to make informed choices.

How do parabens disrupt endocrine systems?

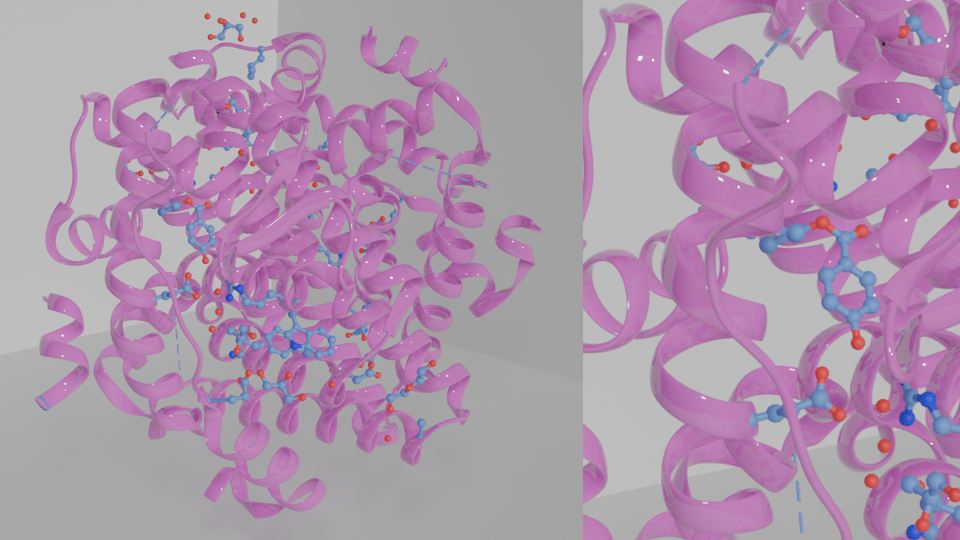

Cells have receptors which bind to specific molecules, and this action initiates intracellular signals that can change the expression of certain genes. The ultimate purpose of cellular signalling is to change the behaviour of the cell. Parabens can bind with a range of endocrine receptors, but oestrogen receptors are a well-known target.

Parabens have oestrogenic activity because their structure allows them to interact with the three types of oestrogen receptors (ER). ER alpha and ER beta are two receptor isoforms, meaning they are functionally similar but not structurally identical, and they reside inside the cell. Another type of oestrogen receptor is GPER1, which is bound to the membrane of the cell. When oestrogen molecules such as estrone, estradiol, estriol, and estetrol bind to oestrogen receptors, intracellular signalling cascades are initiated, which can change the expression of oestrogen-responsive genes.

Parabens mimic oestrogen and can trigger inappropriate and more frequent signalling events even in the absence of oestrogen. Therefore, activation or deactivation of certain genes can alter cellular behaviour, potentially manifesting a variety of diseases. That said, how does the structure of a parabens enable this interaction? Let’s look at the research.

How do parabens interact with oestrogen receptors?

A 2022 study demonstrated how paraben alkyl sidechains could stimulate and interact with oestrogen receptor ligand binding sites in a stable conformation due to van der Waals forces. They also showed how oestrogenic activity increased as the length of the alkyl chain increased (methylparaben < ethylparaben < propylparaben < butylparaben), and the most oestrogenic paraben they found was benzylparaben. Similar results were demonstrated from a study by Watanabe et al. (2013), who showed that the oestrogenic agonist activity was dependent on the length of the alkyl sidechain. They found that stimulation of ER alpha and ER beta was the strongest with pentylparabens, hexylparabens and heptylparabens, which have larger alkyl sidechains.

Investigating a different approach, a group at Longwood University suggested that parabens might bind to the oestrogen receptors because of their phenol ring. In the study they substituted and added different chemical groups onto the ring, and found that these changes blocked the paraben from connecting with the ER alpha receptor binding pocket. But here’s something even better: those same modified parabens actually worked better at preventing microbial growth than traditional parabens! That means there are safer alternatives out there. Pretty cool, right?

What’s the link between parabens and disease?

Endocrine disruptors such as parabens have been associated with reproductive issues such as Endometriosis and Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) as well as infertility. For example, a study by a group at Berkley observed that peripubertal concentrations of methylparaben were associated with earlier breast development, pubic hair development and menstruation in girls, and additionally, propylparaben was also associated with earlier pubic hair development in girls and gonadarche in boys.

One of the biggest concerns about parabens is their possible link to cancer. We’ve already discussed how parabens interact with oestrogen receptors and can mimic oestrogen. Normally, oestrogen helps cells to function, grow and divide through switching on genes that kickstart DNA replication and cellular growth. The problem is, if parabens trigger the oestrogen receptor’s activity too much, they could push cells to grow and divide uncontrollably, which are both classic indicators of cancer.

Before you panic, it’s important to know that parabens don’t directly cause cancer. Rather a lot of research, however, both in test tubes (in vitro) and in living organisms (in vivo), suggests concern that their oestrogen mimicry may contribute to the development of cancer.

Let’s investigate this more.

A recent in vivo study caught my eye. These researchers observed female mice exposed to methylparaben and propylparaben at levels considered safe by FDA standards. The paraben-exposed mice developed significantly larger mammary tumours compared to the control group, which points to the cancer-promoting potential of these chemicals and also questions such relaxed regulatory paraben allowances in products.

An even more fascinating study was recently published in the Journal of the Endocrine Society and revealed that breast cancer cell lines of West African ancestry were more sensitive to parabens than those from European ancestry. What’s really surprising is that methylparaben, the one labelled as the “safer” and less oestrogenically active, significantly ramped up the expression of key molecules driving cell growth, such as the progesterone receptor and cyclin D1. But only in West African cell lines and not in European ones. For me, this study really shines a light on how biology is not a “one-size-fits-all” concept and highlights how essential inclusivity is in research and regulation-making. There’s a mountain of research exploring the risks linked to parabens, but here’s where things get tricky…

Can lab results reflect real life?

One of the biggest limitations of the paraben safety debate is the heavy reliance on rodent and in vitro studies instead of epidemiological research based on real-world population data. This raises the crucial question: can we really apply lab findings to humans?

That’s not to say the research we’ve talked about is incorrect or invaluable. In vitro studies offer important insights without having to use living organisms, while in vivo studies show us how parabens are absorbed, distributed, metabolised, and excreted in living organisms.

The epidemiological research that does exist offers mixed results. This is partly because it’s tough to pin down a cause-and-effect relationship between parabens and disease, especially as there are so many variables involved. For example, Liuyun Gong and colleagues used large population datasets in a 2020 transcriptome-wide association study, where they analysed gene expression profiles, and found that methylparaben exposure was correlated with a higher risk of breast and cervical cancers. On the flip side, a cross-sectional study published this year looked at data from non-institutionalised US population data between 2005 and 2014, but didn’t find any significant association between parabens and breast cancer in women over 20.

Here’s another twist. A study of Japanese university students found that a higher urinary paraben concentration and parabens with higher oestrogenic activity were inversely related to shorter menstruation cycles, hinting at possible fertility implications. But then, a cohort study conducted at the Department of Environmental Health, Harvard, on women undergoing IVF showed no connection between urinary paraben levels and fertilisation rates, embryo quality or oocyte counts.

Unclear, right? These examples are just drops in a vast ocean of research, but the bottom line is that it’s a complex, messy grey area. What’s clear is that far more robust epidemiological studies are needed to truly understand the relationship between parabens and disease. Especially those that focus on realistic human exposures, the mixtures of different parabens in products, physiological concentrations, and multi-generational effects.

So, what now?

Wow, we’ve discussed a lot of information! It’s quite overwhelming as there is so much conflicting evidence linking parabens to the development of disease. Whilst research can be insightful, it often ends up being quite niche and not fully reflective of real-world conditions. That being said, I think it’s worth being mindful about the ingredients in the products we use every day and the regulations that govern our safety. I hope this discussion has broadened your knowledge about paraben research and endocrine disruptors. The truth is, there’s a lot that we don’t know, so before you moisturise, spray, or swipe, take a moment to check the label and the science.

About the author

Hi, I’m Dalia! I’m a Healthcare Scientist Practitioner for the UK Health Security Agency (UKHSA) with a BSc in Medical Biochemistry from the University of Manchester. But more importantly, I love science communication and breaking down the science behind social media headlines. Want to connect? Contact me through my LinkedIn.

Discover more from Research Hive

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.