Author: Paul Humphreys

One of the greatest promises of tissue engineering and regenerative medicine is the ability to generate functional organs for transplantation. Pluripotent stem cells (PSCs), derived from IVF embryos or reprogrammed adult cells, have the capacity to form any cell type and therefore may potentially provide the source of cells required for tissue engineering. Although many of the intricate signalling pathways that lead to specific cell types have been uncovered, building complete organs is much more complicated. Different cell types need to be precisely organised, blood vessels need to be grown and, most importantly, each component must harmoniously function as intended.

Many research groups have described the development of PSC-derived ‘organoids’ in a dish; a small mass of different cell types that replicate some of the organisation and function of the desired organ. Although useful for disease modelling and drug screening, PSC-derived organoids only represent an early stage of the organ’s development. Therefore, a significant therapeutic challenge is to stimulate maturation of PSC-derived tissues to a point that would enable integration, function and possible repair in an in vivo, or within a living, environment.

A case study: Kidney engineering

Around 5 million people worldwide suffer from end-stage kidney disease (ESKD), which describes any patient that requires long-term dialysis or transplantation. The ability to grow replacement kidneys in the lab would dramatically relieve the substantial medical and economic burden of ESKD. Studies have previously generated ‘mini-kidney’ organoids, but these lack mature kidney structures such as functional nephrons that perform the critical function of blood filtration.

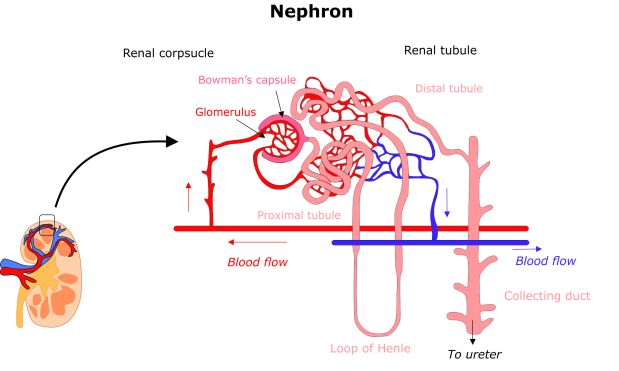

Nephrons are drooping branch-like structures that consist of two main components: renal corpuscles, which act as filtration units, and renal tubules, which collect the filtrate and process the waste as urine. Blood flows through a network of capillaries called the glomerulus into the Bowman’s capsule within the corpuscle. Filtered fluid then runs into the renal tubules, where it is further processed by endothelial cells lining the tubule walls. Water and other crucial molecules are then reabsorbed into the circulation whilst other metabolic waste products are further exchanged to be collected into the renal collecting duct at the end of the tubule and processed as urine.

An overview of a nephron. Adult kidneys contain millions of identical structures to filter blood.

A recent study led by Dr Ioannis Bantounas, a Post-Doc from Prof Sue Kimber’s group in Manchester, may have taken the first steps in the generation of functional nephrons from PSCs. The researchers firstly differentiated PSCs towards immature kidney precursor cells through stimulation with a cocktail of growth factors and differentiation growth medium. The kidney precursor cells expressed many of the markers associated with embryonic kidney tissue and were able to form 3D organoids that allowed further maturation. However, organoids within the dish could not progress to a functional tissue-like structure due to the lack of blood vessels.

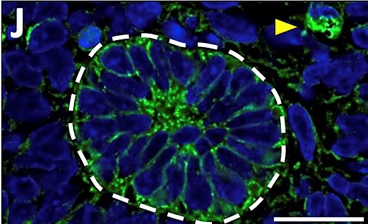

A section of a PSC-derived ‘mini-kidney’ tubule. The green colour represents the fluorescent dye that has been filtered out of the blood by the ‘mini-kidney’. The yellow arrow shows the dye in a blood vessel.

To address this, the researchers implanted the kidney precursors into the backs of immunocompromised mice. After 3 months they observed remarkably mature ‘mini kidney’ structures, including components of the renal corpuscle and tubule. Most crucially, cells appeared to generate mature glomeruli complete with blood vessels. To test the function of the ‘mini kidney’, the researchers injected the mice with a fluorescent dye to determine whether the PSC-derived tissue could successfully filter blood. Indeed, they observed the dye be filtered out of the mouse blood to be collected within the PSC-derived tubules as a urine-like substance, indicating the functionality of the ‘mini kidneys’.

This research demonstrates the bridges that need to be built between generating specialised cell types from PSCs and organising them into functional tissue that may be transplanted. Generating organs within a laboratory environment is a highly complex process; cells receive many chemical and physical cues from their environment, many of which we still don’t fully understand. This reality is outlined in this work, where the kidney precursor cells were only able to fully mature once in an in vivo environment. Although this work is very promising, it still represents just the first steps. Our kidneys consist of millions of nephrons, compared with the few hundred the PSCs managed to make. In addition, the ‘mini kidneys’ did not need to cope with the high rate of blood flow required in the kidneys to filter over 150 litres of fluid every day. However, this research does provide a proof-of-principle that we may yet be able to grow our own organs in the near future.

Read more:

http://www.cell.com/stem-cell-reports/abstract/S2213-6711(18)30034-1

https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/kidney-disease/

Discover more from Research Hive

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.