Author: Paul Humphreys

The human body can be compared to a well-oiled machine with tissues acting as individual components that function both independently and harmoniously. However, this comparison is only apt if the hypothetical machine performs certain tasks more efficiently at certain times of day and shuts down completely if you attempt to leave it on for extended periods of time. It is becoming increasingly accepted that a large number and variety of bodily functions are controlled by the circadian (or body) clock; a biochemical oscillator that synchronises to the light of a solar day, or 24 hours. The circadian clock initiates and maintains circadian rhythm, which describes the oscillatory function of transcriptional regulators that are intertwined with cellular metabolic processes and behaviour throughout the day. Desynchronisation of the clock requires it to reset itself through environmental cues, most commonly light, and you may have experienced rhythmic disruption yourself if you ever had jet lag.

The transcriptional clock

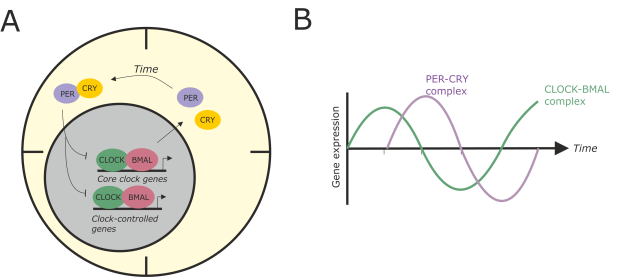

A – A summary of the transcriptional circuit that controls the circadian clock. B – A graph to summarise the activity of the two core circadian complexes during the day.

The clock works by activating the expression of specific genes at different times of day through a feedback circuit consisting of four core proteins; CLOCK, BMAL, PER and CRY (A). In the morning, CLOCK and BMAL form a complex that activate clock-controlled genes, with some examples including the release of hormones, feeding or fasting and heart, liver and gastrointestinal activity. In addition to activating circadian genes, the CLOCK-BMAL complex also activates the expression of PER and CRY which are released to the cytoplasm and accumulate throughout the day. When sufficiently accumulated by the evening, PER and CRY form a complex that enter the nucleus to inhibit the activity of CLOCK and BMAL, bringing an end to the activation of both circadian genes and PER and CRY themselves. Overnight, the level of PER and CRY fall below a threshold, which allows CLOCK and BMAL to begin their activation and the circadian loop again during the next day (B).

Relevance of the clock in disease

Disruption or dysfunction of the clock feedback circuit is linked to many diseases including metabolic, cancerous, neurodegenerative and mental health diseases, many of which are age-related where the strict maintenance of the clock breaks down. Manchester is home to the largest community of biological timing research in Europe, with researchers investigating the molecular mechanisms and homeostasis of the clock, its influence on the brain and the potential for therapeutic targets.

For example, one of the disease targets of the Manchester research centre is the common joint disease osteoarthritis; a debilitating and painful disease that occurs in later life or after a significant injury. During osteoarthritis the cartilage that covers the ends of bones in joints becomes degraded and cannot repair itself, thus leading to inflammation and irreversible structural changes within the joint. The leading treatments currently available are full joint replacements or autologous chondrocyte transplantation, where clinicians remove a piece of cartilage from another area and transplant it into the damaged joint. Neither treatment is permanent and both are associated with their own issues.

A recent study, conducted in Manchester, demonstrated that a core component of the clock, BMAL, is an essential regulator of cartilage homeostasis and repair. Specific ablation of BMAL in chondrocytes (cartilage-generating cells) in a mouse model resulted in the breakdown of joint cartilage in a presentation of osteoarthritis-like symptoms. The authors suggested that breakdown in circadian rhythm with age could be considered a significant risk factor for osteoarthritis and therefore, manipulation of the clock therefore may be a therapeutic target. I spoke to Mark Naven, a PhD student in Qing Jun Meng’s group, who is looking to manipulate circadian rhythm in pluripotent embryonic stem cell differentiation in order to enhance their chondrogenic potential. The differentiated stem cells would then be transplanted into a patient.

How are you specifically using circadian rhythm?

“Pluripotent stem cells are arrhythmic but become rhythmic as they differentiate into different adult cell types. I’m interested in the molecular mechanisms of how the clock ‘switches on’, and how these mechanisms can be manipulated. When we differentiate the cells, the circadian rhythm of each cell is out of phase with each other as there are no natural environmental cues that synchronise them. I use chemical and temperature-based techniques that synchronise the rhythm, which we then hope will improve the cell differentiation.”

How can circadian rhythm be utilised in a therapy?

“Every individual has potentially different ‘chronotypes’, which simply means that every person’s circadian rhythm is in a slightly different phasic cycle. An example of this is how different people have the propensity to go to sleep at different times of day. As described earlier, different cellular functions are active at different times of day, as controlled by the circadian clock, and this includes repair and healing of injuries.

When transplanting cells, or indeed tissues or organs, it may be important to synchronise the circadian rhythm to an individual’s chronotype as well as perform the operation at a specific time of day. Therefore, when the transplant occurs, the body is at its most efficient to repair any damage and incorporate the transplanted cells.”

Useful links:

Manchester Biological Timing Centre twitter

Manchester Biological Timing Centre website

Discover more from Research Hive

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Can our body clock help to repair injuries or cure disease?”