Author: Jo Sharpe

It is hard to avoid the sensational headlines popping up here, there, and everywhere: “Blocking brain inflammation ‘halts Alzheimer’s disease‘”, “The foods that might help with dementia”, and my personal favourites “Dementia: Drinking wine can cut risk of brain inflammation” and “Turmeric health benefits: Curry spice could hold key to combating Alzheimer’s”. Whilst it may not be entirely true that we can fight dementia simply by changing our eating habits, there is some science lurking behind these claims, and scientists at Manchester are at the forefront of a rapidly growing field.

Chronic inflammation of the brain and associated tissue, termed neuroinflammation, is a hot topic in the news and a focus of research groups worldwide.

Inflammation is a physiological and necessary response to tissue injury or infection. The release of pro-inflammatory cytokines is vital for the recruitment of immune cells to destroy infected or dead cells. Pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines coordinate and manage the immune response, maintaining a balance between destroying invading pathogens and sparing the body’s own tissue. It is when this delicate balance is knocked out of kilter that inflammatory diseases can develop. Excess or aberrant inflammatory signalling leading to acute or chronic inflammation in sterile conditions can result in tissue damage, when the immune system fails to “switch off” and attacks your own cells. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s Disease are caused by chronic inflammation of the digestive tract and are debilitating lifelong conditions which can have life-threatening complications.

How can inflammation affect the brain?

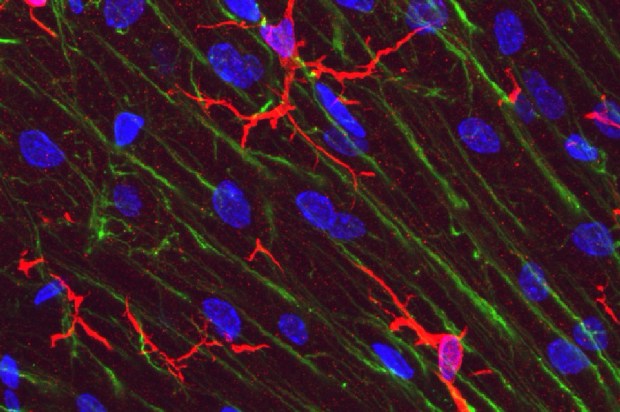

The brain is separated from the blood network by the blood brain barrier (BBB), meaning that immune cells of peripheral tissues cannot penetrate the central nervous system (CNS). However, the brain has its own resident immune cells known as microglia, capable of initiating and sustaining an inflammatory response. Microglia are vital for brain development by facilitating synaptic development and plasticity; they secrete factors that promote the growth and differentiation of new neurons and synapses and actively prune synaptic terminals. In a “resting” or “surveillance” state, microglia form a network ready to evoke an innate immune response should they become activated. Just like peripheral macrophages, microglia have the receptors capable of detecting foreign antigens and inducing an innate immune response and thus inflammation. An inflammatory environment can develop in brain tissue following injury which initiates an immediate release of pro-inflammatory cytokines. This can exacerbate the damage and lead to break down of the BBB and white blood cell infiltration. This may seem counterintuitive, but short term inflammation is necessary to allow clearance of cell debris from the site of injury. It is when this inflammation becomes long term and chronic that problems arise. Chronic inflammation leads to further cell death and damage radiating from the site of injury.

In addition to injury, simply growing older is a cause of chronic neuroinflammation. Even in a healthy aged brain, there are increased levels of pro- inflammatory cytokines and activated microglia. The homeostatic imbalance between pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines is linked to age-related cognitive decline, and is considered one factor that increases the risk of developing neurodegenerative diseases as we age. Inflammation has been shown to affect neuronal excitability and pro-inflammatory cytokines have direct effects on neuronal function and synaptic transmission, which may contribute to the cognitive symptoms associated with certain diseases.

Microglia in rat. Cerebellar molecular layer in red, stained with antibody to IBA1/AIF1. Bergmann glia processes are shown in green, DNA in blue.

There is growing evidence supporting a role for inflammation in Alzheimer’s disease progression. Here at Manchester, a collaboration between many principal investigators and their respective groups, collectively known as the Brain Inflammation Group, are investigating the role that neuroinflammation has in disease progression and how it can be targeted therapeutically.

Of particular interest to many researchers within the group is the NLRP3 inflammasome. Inflammasomes are multiprotein complexes that coordinate inflammatory responses by activating the pro-inflammatory cytokines interleukin-1b (IL-1b) and IL-18 in response to pathogens and sterile stressors. The NLRP3 inflammasome is the best characterised inflammasome and is a key player in the sterile inflammatory response, regulating inflammation in many neurodegenerative disorders. For example, NLRP3 recognises amyloid oligomers to trigger neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s Disease. The NLRP3 inflammasome has been suggested as a promising target for anti-inflammatory drugs, given its involvement in multiple neurological conditions including multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s Disease, and epilepsy.

Targeting the inflammasome

Jack Rivers-Auty, a BBSRC Future Leader Research Fellow in the Brain Inflammation Group, wrote an excellent blog explaining the story that led to a class of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) known as the fenamates being identified as a potential therapeutic for Alzheimer’s Disease. The hypothesis that these non-classical NSAIDs have inhibitory activity on the NLRP3 inflammasome was first tested by PhD student Mike Daniels, who recently graduated. Following on from this, Auty and his colleagues tested mefenamic acid in a mouse model of Alzheimer’s Disease and found that brain inflammation was reduced and memory loss reversed.

This was incredibly exciting as this class of drugs have been used for pain relief in the clinic for years and as such are FDA approved, meaning the time it would take to validate and approve these drugs for clinical use would be greatly reduced.

It is clear that the Brain Inflammation Group are producing exciting research and PhD students within the group are heavily involved in their success. In the last month, a paper revealing the role of chloride ions in regulating the NLRP3 inflammasome was published, and earlier this year the group revealed their characterised tool kit for the interrogation of NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent responses. In addition to this, three 1st year PhD students recently published a comprehensive review covering the NLRP3 inflammasome and its potential as a drug target. The review, written by Tessa Swanton and James Cook of the Division of Neuroscience and Experimental Psychology, and James Beswick, based in the Division of Pharmacy and Optometry, recently made the front page of SLAS Discovery.

The group’s research brings together expertise in a number of different diseases such as stroke and Alzheimer’s Disease, as well as providing a wide variety of skills and knowledge in different areas, including the involvement of medicinal chemists to allow the targeted development of new small molecule drugs. This collaborative effort has allowed significant progress to be made in the field of neuroinflammation and brain disorders.

The recent flurry of neuroinflammation research may not provide strong evidence that we should be eating chicken tikka masala for dinner every night… Nevertheless, it is certainly encouraging and suggests that therapeutic strategies to tackle these devastating disorders may be on the horizon.

Discover more from Research Hive

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.