The human brain is the most complicated computer on the planet. Its hardware consists of an intricate concoction of cells that convert countless electrical and chemical signals every second into each thought, decision or action that we make. Our brains are the reason we have sent rockets to the moon and developed vaccines to eradicate disease. But just like a computer, sometimes the human brain will glitch. Other times it can malfunction. And the older the brain gets, the more likely it is to do just that.

Advances in medicine have led to the global average life expectancy increasing drastically, roughly doubling in the last 100 years alone. It comes as little surprise, therefore, that we are experiencing a surge in the prevalence of age-related diseases of the brain.

We only need to consider a handful of these diseases to grasp the full extent of the problem. Alzheimer’s disease is the most common form of dementia, caused by faulty proteins building up and forming plaques and tangles in our brain. These plaques and tangles cause the nerves in the brain to die, and once they die they don’t come back, causing the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease such as memory loss. Strokes occur when the oxygen supply to the brain is disrupted, and without oxygen, nerves in the brain begin to die.

Every six seconds, stroke kills one person.

Every six seconds, two people develop dementia.

Clearly these diseases pose huge challenges, and they exist because, unlike computers, humans don’t have a reset button. We can’t just be switched off and on again. We need to find answers to these questions, and we need to find them quickly.

One such answer may lie in the common ground that underpins both Alzheimer’s disease and stroke: inflammation. Inflammation is a response by our bodies to help fight infections, but inflammation at the wrong time or in the wrong place can actually make things worse. This is exactly what we think happens in the brain when someone starts to develop Alzheimer’s disease, or when someone has a stroke.

Inflammation in the brain can help and hinder us.

Unfortunately, we really just don’t know enough about inflammation in the brain, called neuroinflammation, to be sure whether it is the hero or the villain. It might even alternate between the two at varying stages of different diseases. In particular, we suspect that an important inflammatory protein called NLRP3 might be pulling some of the strings.

This is where my latest research comes in. I’ve been trying to find new ways of understanding inflammation in the brain. How is NLRP3 protein activated? How is it controlled? What are the consequences of inflammation in the brain?

I’ve started to answer these questions using an interesting model called an organotypic brain slice culture. Essentially, I took a chunk of mouse brain and grew it in a dish for a week in the lab. Once I’d done this, I made these brain chunks become inflammatory. I find this model so fascinating because it is an actual piece of brain. I can simulate the complexity of the whole brain. Other brain models can be too simplistic to do this, as they’re normally just a single layer of cells.

Once I caused the brain cultures to become inflammatory, I dug a little deeper to work out which cells in the brain were responsible, which inflammatory molecules were being spewed out by these cells, and what this might have done to neighbouring cells. Not only this, I could actually watch this happen with my very eyes! By using an advanced microscope, I saw these cells reacting angrily to my treatments, changing shape and eventually dying.

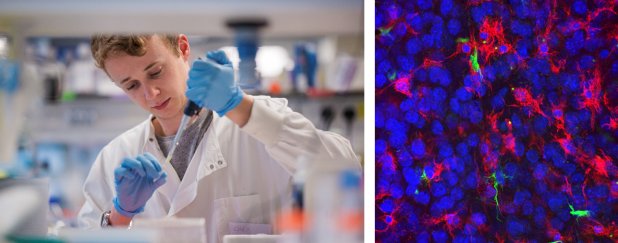

Dr Chris Hoyle in the lab (by Dr Arthur Yushi) // Genetically-modified brain slices under the microscope showing nuclei, microglia and a key inflammatory proteins

Not only did I use normal brain tissue, but I also took brain tissue from mice that have been genetically modified to make a key inflammatory protein inside the cell fluorescent. This meant that, rather than just watching the cells, I could specifically watch this individual protein down the microscope to see how it was behaving!

It’s pretty clear that inflammation is seriously important. My research should help to lay the foundation of our understanding of neuroinflammation. Once this foundation is in place, we can then progress to looking at neuroinflammation in specific diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease and stroke. Could targeting inflammation in our brains really represent a promising option to tackle these diseases and improve the lives of the people who suffer from them? Whether it ultimately does or doesn’t turn out to be an effective target for treatment. I’m sure you’d agree that it’s worth trying to find out.

Research paper – https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/imm.13221

To find out more about the lab, visit – https://www.braininflamelab.org/

Discover more from Research Hive

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.