By Jo Sharpe

Fruit flies: it’s hard to find a soft spot for these irritating insects, but stick them in a lab and they take on a new importance.

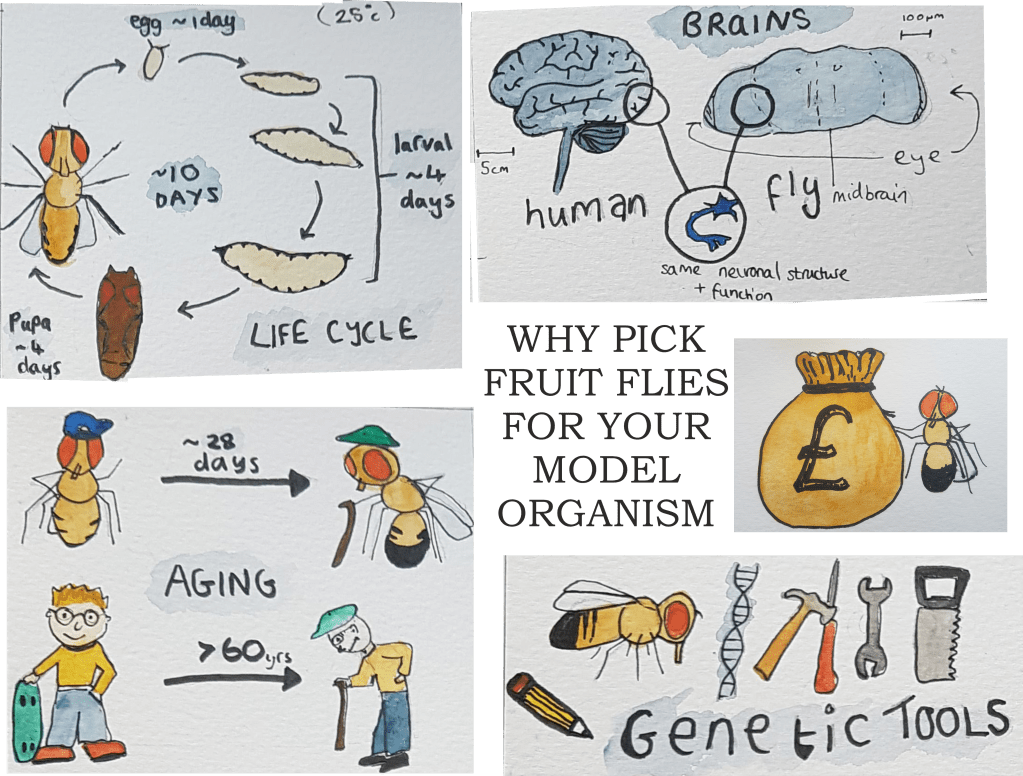

The fruit fly, Drosophila melanogaster, is more often associated with an overflowing kitchen bin than a lab, but in fact it’s a great model for understanding neurodegenerative disease – and here’s why:

- They are cheap and easy to look after

- A short lifecycle allows genes to be shuffled around quickly

- A lifespan of around three months means studying aging is a piece of cake compared to waiting years for mammals

- The underlying neuronal architecture is very similar to a human’s, despite their brains being one million times smaller

Here at Manchester we have the wonderful Fly Facility providing communal resources and expertise. A recent publication by West et al., is a great example of how flies can be used to understand human disease. I might be biased (I am an author) but this paper is super interesting and has some pretty pictures in so you should definitely check it out.

However, I do understand that not everyone wants to sit and read a paper cover to cover when it is completely irrelevant to their research area…

Good news! This blog post will give you all the juicy content without any of the jargon.

Background: the disease

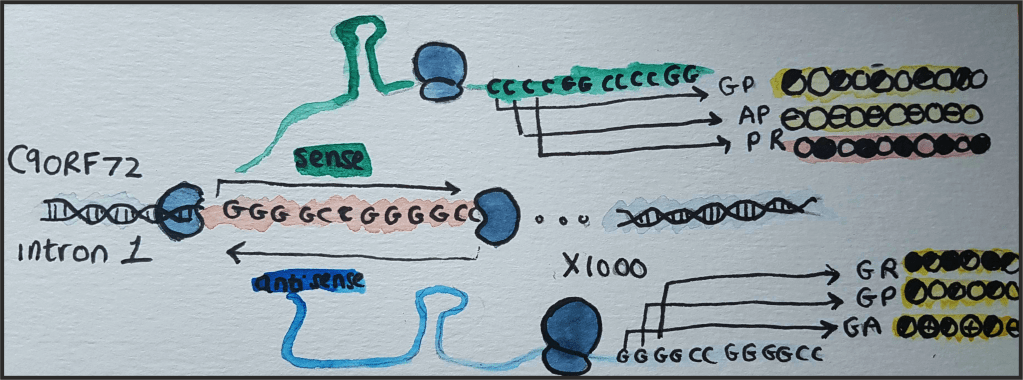

A mutation in the first intron of the C9orf72 gene is the most common cause of frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and motor neurone disease (MND), two deadly and devastating neurodegenerative diseases.

This mutation is relatively unusual because it is an expansion of a stretch of DNA; a sequence of six bases (GGGGCC) is repeated over 1000 times and causes FTD, MND, or a combination of both. The levels of endogenous C9orf72 transcript are reduced, but loss of function is not thought to be the main cause of neurodegeneration.

The repeat is transcribed and translated via a form of translation that does not require a start codon. Translation occurs in all six frames, producing five different dipeptide-repeat proteins (DPRs). They comprise two amino acids (dipeptides), repeated over and over again. The DPRs produced are: alanine-proline (AP), glycine-alanine (GA), glycine-arginine (GR) , proline-arginine (PR) and glycine-proline (GP, produced by translation in two of the six frames).

Background: this study

DPRs are generally considered to be the main contributor to toxicity but the mechanisms underpinning neurodegeneration remain unclear.

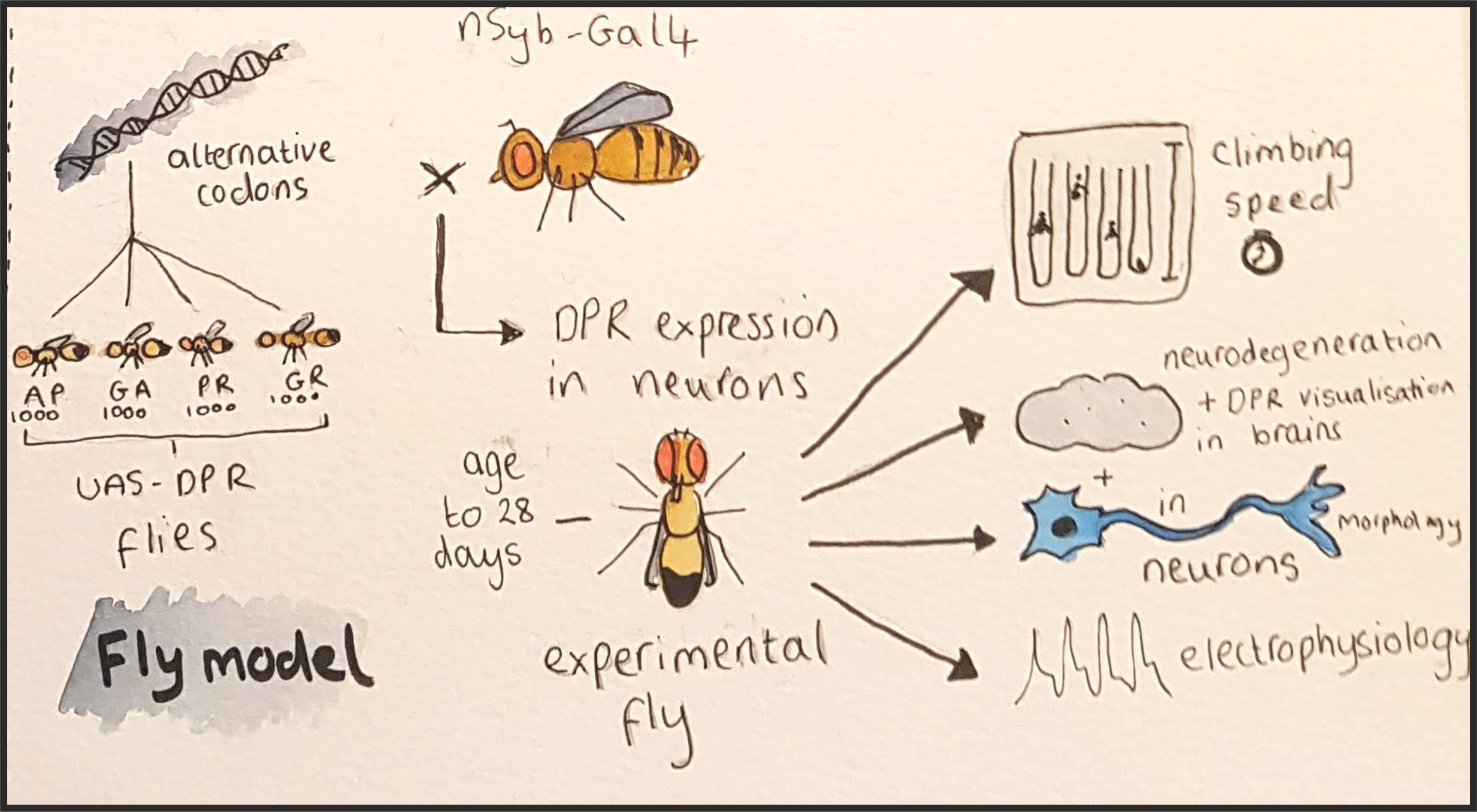

Fly models have been critical in developing our understanding of the role of DPRs in FTD and MND. However, they have a potential flaw – the repeat length of the DPRs. In humans there are in excess of 1000 repeats, yet pre-existing fly models express DPRs of only 100 repeats or fewer. This is due to the difficulty of working with long repetitive DNA.

It raises an important question: does size really matter?

This is one of the questions we set out to investigate. It is important to know how physiologically relevant your model is in order to critically evaluate your findings.

Results

After successfully engineering four separate fly lines each expressing a different DPR with over 1000 repeat units in the brain, the question was: how are these flies different from the other models, and does this have ramifications for how we use them in the future?

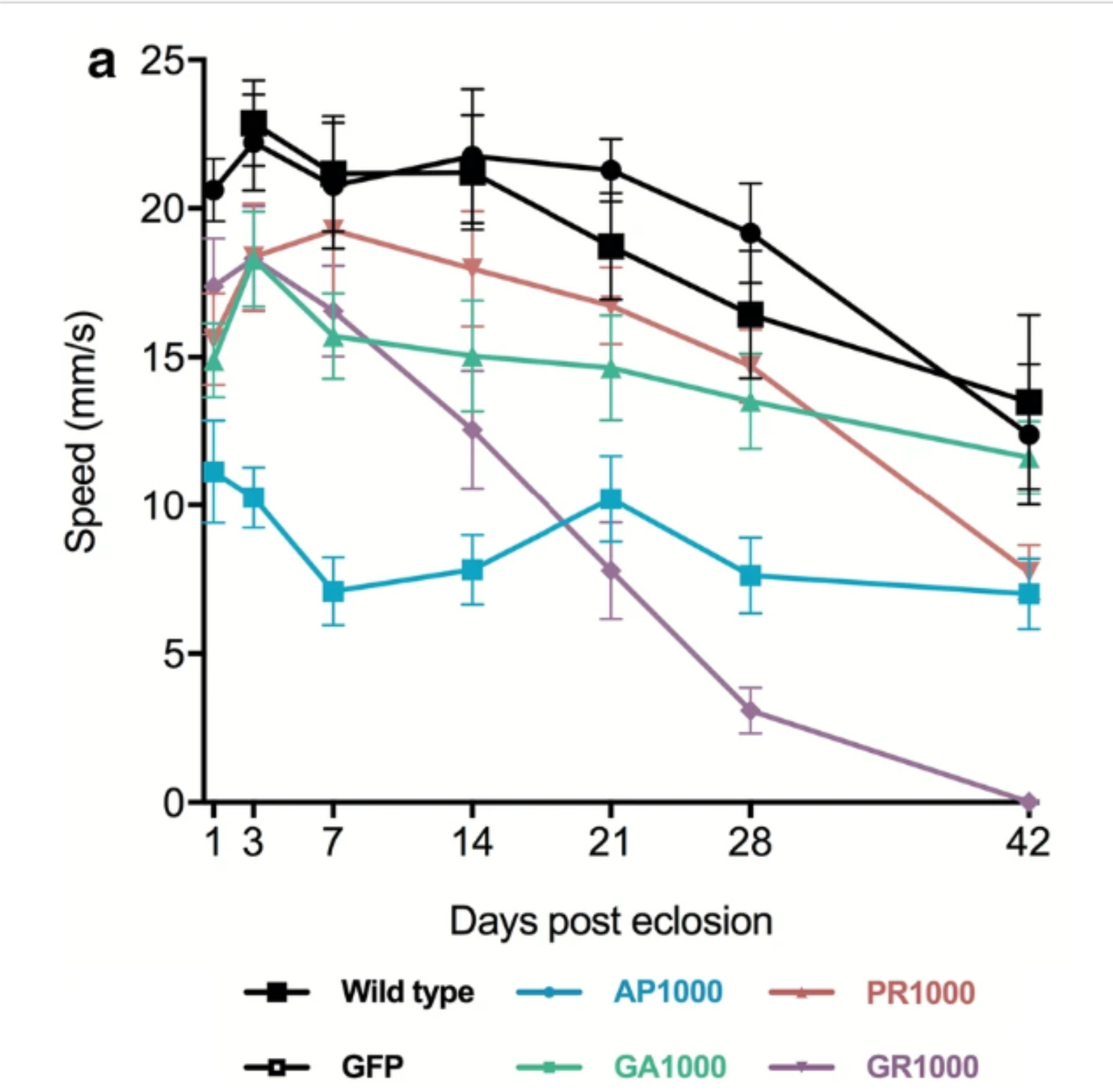

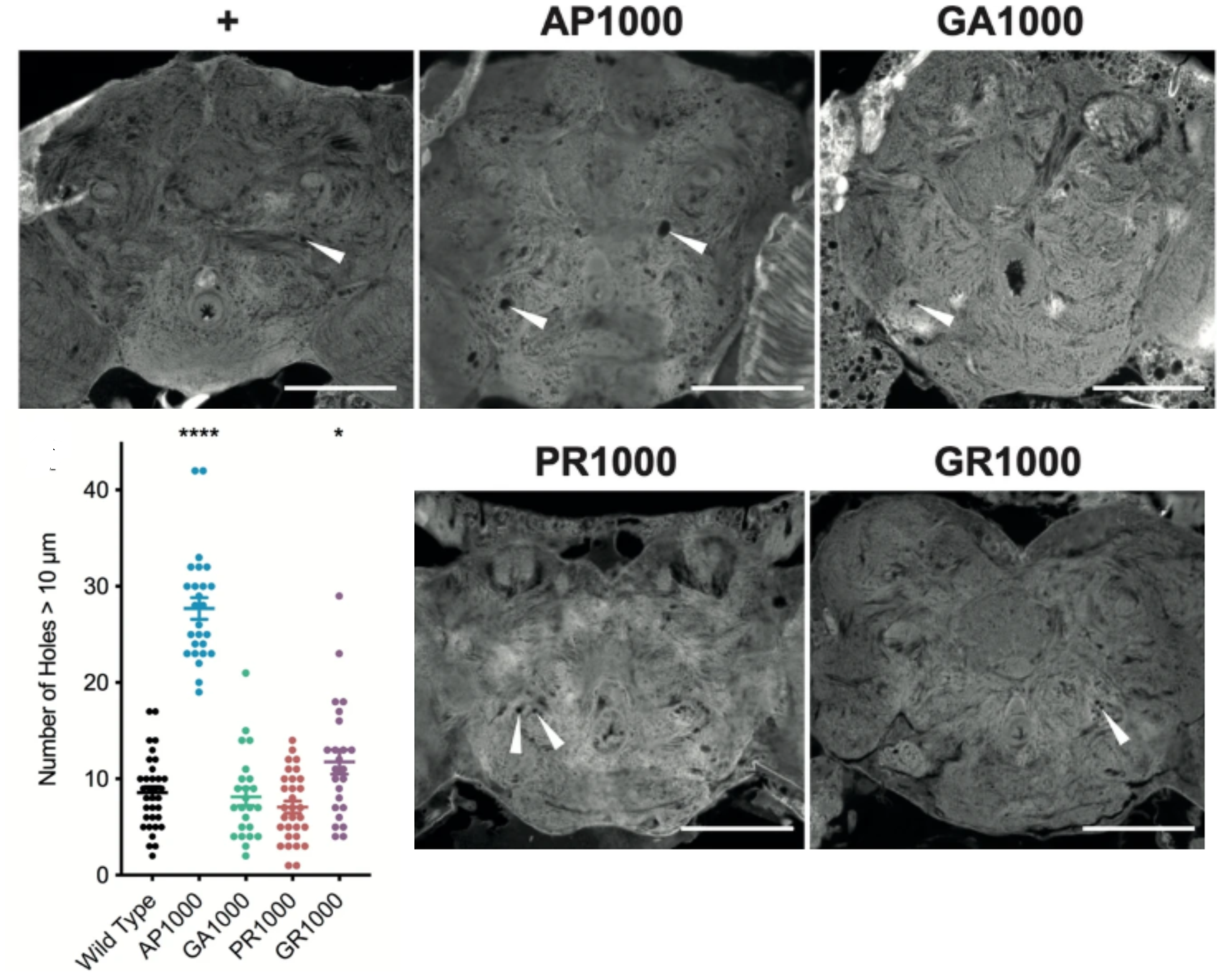

Fly brains were studied to look for the structure and localisation of the DPRs and neurodegeneration (holes in the brain!). Phenotypes such as climbing speed, lifespan, and electrophysiological function were measured.

Interestingly (if I say so myself), the new DPR models have distinct phenotypes that, crucially, change with age. This is important because FTD and MND are diseases of later life.

In the literature, GR and PR are often cited as the most toxic species with AP being completely benign, but our data does not support this. Perhaps most strikingly, although AP flies live longer, they have larger and more numerous holes in their brains, and their climbing speed is consistently slow. In contrast, GR and PR flies begin life sprightly and agile, but decline rapidly with age.

However, length isn’t the only consideration when striving for physiological relevance. In people with the C9orf72 mutation, all the DPRs are expressed together in the same neuron. This is in contrast to these and other DPR fly models which express only one at a time. This is useful for teasing out the differences between DPRs but it is important to remember that this is not how they are in humans.

What next?

Testing different combinations yielded some interesting and admittedly confusing results. The data suggested that certain phenotypes only appeared when arginine -rich (GR and PR) are combined with alanine-rich (AP and GA). We hypothesised that the severe degeneration seen in GR and PR may be made worse by the basal level of dysfunction caused by alanine-positive DPRs. I am now continuing to probe this topic and try and work out what is going on inside neurons to cause these differences.

To summarise…

You can swat flies when they haunt your fruit bowl, but don’t forget what they do for science!

We hope that our new model will prove useful for future studies into FTD/MND as we share our findings with the friendly Drosophila community.

Discover more from Research Hive

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.