By Matina Shafti

@MatinaPsy

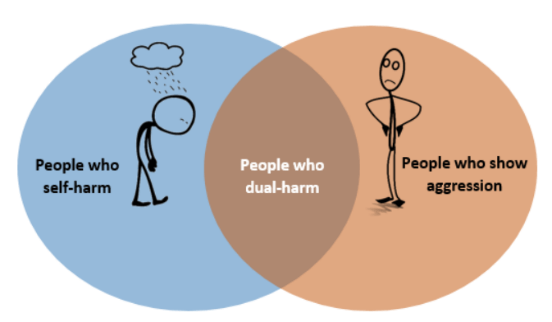

Self-harm and aggression are harmful behaviours that can have severe consequences for both the individual and those around them. These behaviours are prevalent across the world, making it a global health issue. On the surface, it might seem that self-harm and aggression are two completely different behaviours. After all, one is an act against the self, and the other is an act against others. However, research has shown that self-harm and aggression are associated with one another and share many risk-factors, including negative childhood experiences, mental health problems and biological factors. In fact, rather than engage in only self-harm or aggression, many individuals engage in both during their lifetime. The co-occurrence of self-harm and aggression during the course of an individual’s lifetime is called ‘dual-harm’. O’Donnell et al.’s (2015) systematic review of 123 studies highlighted the presence of dual-harm across different populations, including the community, healthcare patients, prisoners, and forensic mental health service users. In most of the studies of harmful behaviours that they reviewed, dual-harm occurred in at least 15% of participants. Dual-harm has been found to be especially prevalent in forensic populations, such as prisoners and forensic mental health service users. Slade et al.’s (2020) study of dual-harm in English prisons reported that 60% of prisoners who had self-harmed, also had a history of aggression. Also, those who self-harmed were 3 times more likely than those with no history of self-harm to be aggressive. This tells us that rather than engage in only self-harm or only aggression (sole-harm), most high-risk offenders will engage in both.

There are people who only self-harm, people who only show aggression, and people who engage in both, referred to as dual-harm

There is evidence that suggests there are differences in the factors associated with dual-harm and sole-harm behaviour. Slade et al. (2020) found that compared to those who engage in sole-harm, prisoners who engaged in dual-harm behaviour spent longer in prison, used more severe methods of self-harm and perpetrated a higher rate and wider range of negative prison incidents, such as fire-setting and property damage. In support of Slade et al.’s (2020) findings, studies have provided evidence that individuals who dual-harm have characteristics that might distinguish them from those who sole-harm. For example, they are more likely to have problems with managing their emotions and behaviours, experienced negative events in their childhood and to show a riskier pattern of harmful behaviours. In light of this evidence, researchers have suggested that those who dual-harm might have unique characteristics that distinguish them from people who only self-harm or who are only aggressive. Rather than simply share the same risk-factors, it might be that in the context of dual-harm, self-harm and aggression share one causal pathway and serve the same purpose for the individual. According to this hypothesis, it might be important for preventative strategies that target dual-harm to be tailored to the unique aspects of this behaviour and the specific needs of the individuals who engage in it.

This brings us to the question…

How do we prevent and reduce dual-harm? The short answer is, we don’t really know. In research and practice, self-harm and aggression have traditionally been thought of as two completely different behaviours. This separation might largely be driven by the opposing perceptions we have about self-harm and aggression. When we think of self-harm, what typically comes to mind is a person who is in great distress and in need of care. On the other hand, when we think of aggression, we tend to think of a perpetrator whose behaviour is completely unreasonable and requires punishment. These different perspectives are mirrored in the literature in which there is little research that has investigated dual-harm behaviour and a lack of agreed, comprehensive framework that explains why self-harm and aggression might co-occur in many individuals. The National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE), which provides guidelines for clinical practice in the UK, has separate guidelines for how self-harm and aggression should be managed. There is no mention of dual-harm, the unique characteristics and pattern of this behaviour and strategies to address it.

There are no national clinical guidelines for dual-harm. How do we best manage people who engage in this behaviour?

When an individual self-harms, strategies are rightfully centred around a care-giving approach in which the focus is on helping the individual and trying to understand them. In contrast, when someone is aggressive, the focus is on protecting others. As a result, strategies tend to be centred around containing and punishing the individual, typically through reduced privileges, solitary confinement or segregation. There is evidence suggesting that compared to those who are only aggressive, prisoners who dual-harm spend longer in prison and twice as much time in segregation and other punishment-orientated programmes. Also, strategies for managing aggression have been shown to actually increase the individual’s risk for future aggression and self-harm. This might tell us that existing strategies are not effective in preventing dual-harm behaviour, possibly due to the insufficient consideration of the co-occurrence of self-harm and aggression in individuals.

Strategies for self-harm focus on understanding the individual and their distress. This is quite different from punishment-orientated strategies that tend to be used to manage aggression

In order to encourage greater consideration of the duality of self-harm and aggression, it is important for us to change our perspective of these behaviours as two completely separate constructs, to being more unified than we had previously thought. This shift in perception can happen by expanding the literature on dual-harm. In the early 1900’s, Freud referred to suicide as ‘aggression turned inward’, suggesting a link between these two behaviours. 100 years later, there is still little research that has sufficiently explored this link. There is a need for future studies that investigate the causal mechanisms, functions and characteristics of dual-harm. Such research can help us better understand how to prevent this harmful behaviour, and that is exactly what I hope to achieve with my PhD. My research aims to extend our limited understanding about dual-harm by examining the psychological mechanisms that might contribute to this behaviour. Specifically, I am investigating the role of personality and emotional functioning in dual-harm within forensic mental health services. I hope that my research can add to the growing literature that is encouraging us to stop thinking of self-harm and aggression as two completely unrelated behaviours in those who dual-harm, but to consider whether they might actually be two sides of the same coin.

If you would like to learn more about other research that is happening at the University of Manchester about the risk, health and social care needs of people in contact with the criminal justice system, check out the Department of Health funded initiative – Offender Health Research Network (OHRN), based at the Faculty of Biology, Medicine & Health.

By Matina Shafti – PhD Candidate – Matina.Shafti@manchester.ac.uk, twitter: MatinaPsy

References

O’Donnell, O., House, A., & Waterman, M. (2015). The co-occurrence of aggression and self-harm: systematic literature review. Journal of affective disorders, 175, 325-350.

Slade, K., Forrester, A., & Baguley, T. (2020). Coexisting violence and self‐harm: Dual harm in an early‐stage male prison population. Legal and Criminological Psychology, e12169.

Discover more from Research Hive

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Self-harm and aggression: two sides of the same coin?”