By Malini Dey

Background to my project

Our bodies are made up of very small live units called cells. Cells are like cities, that are constantly evolving and regenerating, and full of buildings which are represented by DNA (the chemical ‘letters’ that make up the genetic code in the cells). These cells undergo cell division to replace old cells that have died. During this, DNA is replicated (copied). This is controlled by chemical messengers called enzymes.

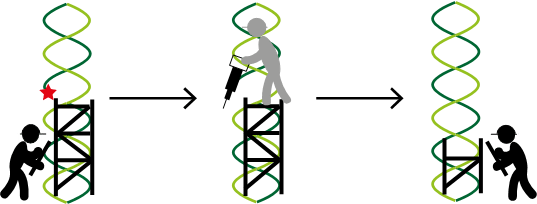

When DNA damage is detected, cell division decelerates and two sets of enzymes, represented as construction workers, work together to repair the damage. One set, poly(ADP-ribose) polymerases (PARPs), are the builders who make poly(ADP-ribose) (PAR) scaffold near the breakage site. This process is called poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation. The other set, poly(ADP-ribose) glycohydrolases (PARGs), are the destructors who dismantle PAR. Key cellular proteins, the machines, access and mend the breakage. These components prevent further damage and keep the cells alive. Under exceptional circumstances, the breakage sites that remain uncorrected cause ‘mistakes’ or mutations in the genetic code. Normal cells have an extremely slow mutation rate.

But, what if DNA repair and replication are disrupted?

An abnormal cellular environment emerges, because the repair proteins frequently contain mutations that causes them to switch ‘on’ or ‘off’ inappropriately. This leads to inefficient repair and replication stress, an accelerated mutation rate, and the cells dividing uncontrollably and indefinitely. As a result, these cells are more dependent on PARPs and PARGs to control DNA damage and remain alive.

PAR dynamics describes the constantly changing and progressing PAR levels over time. PAR levels have commonly been measured in fixed cells. These cells are treated with specific chemicals to retain their shape and structure, and improve their stability for subsequent experiments. However, the biological processes are halted, so PAR levels are presented as a static snapshot. Therefore, we are unsure how PAR levels change over time or how quickly PAR is being made and dismantled.

So the big question is:

Can we measure PAR dynamics in living cells? The short answer is, yes. This is important because PAR levels can be measured more accurately in real-time, and the areas of high and low levels can indicate certain cellular states and processes. However, the current options for measuring PAR dynamics have limitations, so I am looking at alternatives. I will build a PAR biosensor using novel tools called aptamers.

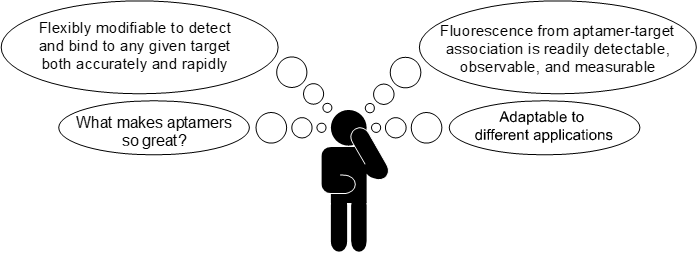

So, what are aptamers? Aptamers are short single-stranded oligonucleotides (strings of chemical ‘letters’), capable of binding to any given target with great precision. They also describe RNA mimics of fluorescent proteins, such that a chemical compound called a fluorophore, fluoresces when bound to the aptamer.

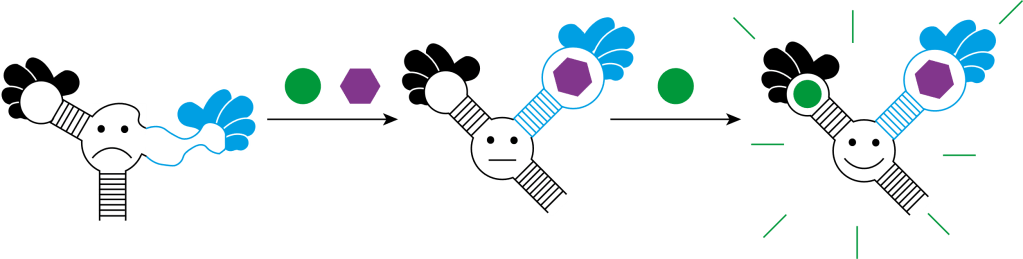

As you can see, aptamers have many advantages. But the most important advantage of aptamers is that they can be used to build a biosensor. I aim to build my biosensor in the form of an aptamer beacon. The schematic below shows how this will work.

The biosensor is composed of an RNA aptamer called Spinach (black) and the recognition module aptamer (blue). The recognition module aptamer undergoes a conformational change upon binding to the target (purple hexagon), with high specificity. This allows Spinach to also undergo a conformational change, so that it binds to a fluorophore called 3,5-difluoro-4-hydroxybenzylidene imidazolinone (green circle), which fluoresces when bound. As a result, the whole system ‘lights up’ to indicate the presence of the target. As you might have guessed, the RNA aptamer is called Spinach, because it shines green light when bound to 3,5-difluoro-4-hydroxybenzylidene imidazolinone.

Why is my project important?

I am interested in looking at the changes in PAR levels over time at the single cell level. The measured levels could indicate irregularities in the cellular mechanisms, that may underlie serious health conditions such as cancer. The general concept of PAR dynamics has been exploited in cancers including ovarian cancer, where PARP inhibitors are commonly prescribed, to stop PAR being made and prevent repair. Furthermore, recent research has suggested that PARG inhibitors could be applied as a potential therapeutic option. PARG inhibitors stop PAR being dismantled and prevent completion of repair. Therefore, my project will also provide an insight into how both inhibitors affect PAR levels in cancer cells.

My goal is to explore fluorescent or other chemically modified and measurable aptamers as ‘PAR biosensors’, capable of binding to PAR and analysing the changes in PAR levels over time, in living cells. In collaboration with the industrial partner Aptamer Group, I will manufacture new tools to study PAR levels, and their effects on DNA repair and replication, in the context of normal cellular physiology and cancer.

Strategy

The first steps are to generate PARylated and dePARylated substrates, and identify the aptamers that bind to the PARylated substrates in collaboration with Aptamer Group. The aptamers will then be fused to Spinach to create a PAR biosensor. The final steps will involve validating and testing the biosensor in living cells.

So far, I have made a GFP-PARP1 recombinant plasmid, transfected this into a model cell line, and analysed GFP-PARP1 expression using fluorescence microscopy and immunoblotting. Afterwards, I affinity purified GFP-PARP1. This involves separating GFP-PARP1 from the rest of the cellular material, using a solid support.

What next?

I will create PARylated and dePARylated states on GFP-PARP1 using PARP and PARG inhibitors, and affinity purify these substrates. I am really excited to investigate this, because I am intrigued to see whether and how these drugs affect GFP-PARP1.

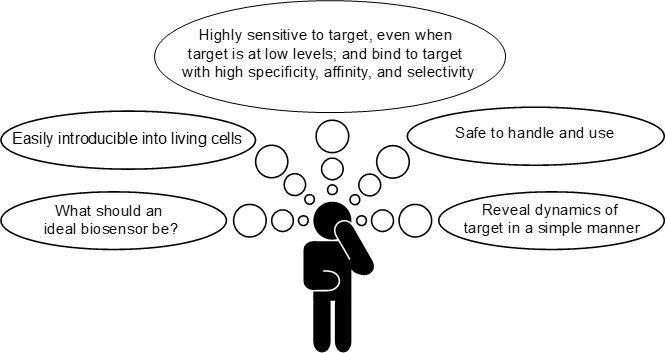

Below describes the qualities of my ideal biosensor:

Summary

I am thoroughly enjoying working on this project. I hope one day my aptamer-based biosensor will provide a useful alternative for measuring PAR dynamics in various living cells.

I would like to thank the Taylor lab, and to Professors Stephen Taylor and Paul Townsend for their continuing supervision, guidance and support. I am very grateful to Aptamer Group for their assistance in making the aptamer-based biosensor.

Discover more from Research Hive

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.