What weighs a third of your body weight and is inhabited by Keanu Reeves? That’s right, the matrix! Okay maybe there’s a bit of a difference between the simulated reality from the 1999 blockbuster and the matrix which I’ll be talking about, but I’d argue my kind of matrix is just as interesting. So interesting in fact, that a new PhD programme at Manchester has been set up to research just that – but more about that later.

The matrix I’ll be telling you about is known as the extracellular matrix or ECM and is found all over your body. It is a huge structure of connective tissue made up of complex glycoproteins like collagen and keratin and acts as the scaffolding on which all your cells reside, connecting them to form tissues and organs. Your body is about 70-95% matrix1; without it you’d be a puddle of cells on the floor with nothing attaching them together. Sounds pretty important – right? The ECM is much more than just a physical scaffold though; it is a highly dynamic structure which is constantly interacting with cells, both signalling to cells to behave in different ways whilst also being shaped and remodelled by them.

One system thought to have important interactions with the ECM (and also the system I’m most interested in) is the immune system. The matrix has an integral role in signalling to immune cells and can cause them to:

- multiply and divide

- migrate to different areas of the tissue

- become activated and cause inflammation

- and a whole lot more!

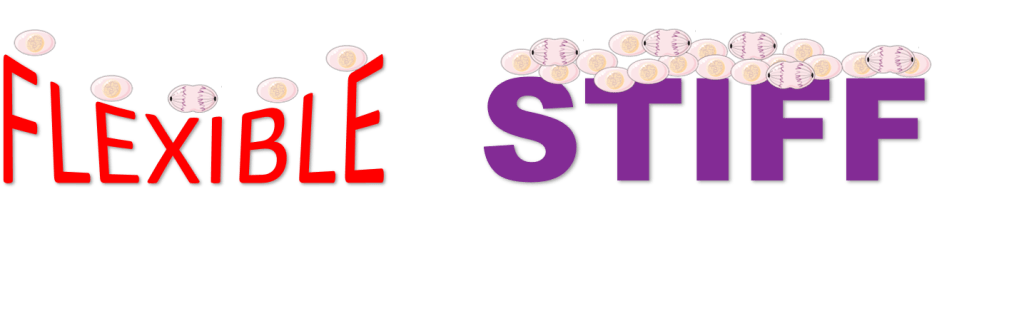

Immune cells can receive signals from the matrix via chemicals such as cytokines and chemokines bound to the matrix, but also from physical properties such as how stiff the matrix is. Cells behave in very different ways depending on how stiff or flexible the material they are sat on is, for example, cells sat on a stiffer matrix tend to multiply and divide much more and die much slower than other cells2. In this way, the matrix has a lot of influence over immune cells and how they behave and can be responsible for causing inflammation in the body, both good and bad.

Not only can the matrix regulate immune cells, but immune cells can also regulate the matrix! Immune cells can cause the breakdown and remodelling of nearby matrix and alter its properties, either directly or indirectly via signalling to other cells. The interaction between the immune system and matrix is important in maintaining a healthy body; they work as a team to maintain homeostasis. An example of this teamwork is when you cut yourself3 – the damage causes the collagen (an ECM component) in your skin to become exposed, which triggers the release of chemicals which draw immune cells to the area. In turn, the immune cells release chemicals which cause inflammation which is essential for the wound to heal. Inflammation allows new ECM to be produced by cells and the wound to contract and close, whilst also killing any bacteria which may have gotten into the wound to prevent an infection. Wound healing is one example of many in which the immune system and the matrix work together to maintain a healthy body. However, they don’t always work together for good.

When something goes wrong in this immune-matrix interaction, disease can occur. Dysregulation of the matrix is central to the pathogenesis of many diseases, such as cancer. In cancer, it’s thought that the matrix is much stiffer than in normal tissue, preventing immune cells from behaving normally and stopping them from attacking the tumour as they normally would4. This allows the tumour to dampen down the immune response and continue growing. As you’ll know by now, the immune-matrix interaction works in both directions, so immune cells can also interfere with the matrix. If immune cells are faulty and become activated when they shouldn’t, they can release proteases5 which break down the matrix and remodel it, changing its properties and altering how it interacts with other cells. This can cause a cycle of signals between matrix and immune cells which make a disease worse and worse. It can be confusing to work out which came first, a problem with the matrix or a problem with the immune system? A bit of a chicken and egg if you will. There are a whole host of diseases caused by faulty immunomatrix, ranging from inflammatory bowel disease to psoriasis, so understanding the interaction between these two systems is incredibly important in working out how to treat and prevent these diseases.

So, what has Manchester got to do with all this? Manchester is home to both the Wellcome Centre for Matrix Research and the Lydia Becker institute of immunology and inflammation; both thriving hubs for research at Manchester. These two centres are beginning to collaborate more and more and combine the fronts of immunology and matrix biology in a really exciting way. This has culminated in a new PhD programme being set up: ‘The Immuno-Matrix in Complex Disease’. This new programme funded by the Wellcome Trust aims to ‘understand common mechanisms underlying complex diseases by studying the interplay between immune cells and the extracellular matrix’. You’ll never guess who one of their new students is – that’s right, it’s me. I was drawn to this programme as it combines the expertise of researchers from matrix biology and immunology in a way I hadn’t seen before. My background is in immunology and through this I saw that research often ignores the context in which the immune cells sit. If we do experiments on cells in a petri dish with no ECM, is it truly representative of how cells would behave in the body, when we know the ECM can impact the way cells behave? This new PhD programme is very exciting and will give us a very different approach to our research. This is a really promising field that could lead to many advances in understanding how the immune system and matrix work together in both health and disease, and I am very excited to get stuck in.

References:

- R. O. Hynes and A. Naba, “Overview of the matrisome–an inventory of extracellular matrix constituents and functions,” (in eng), Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, vol. 4, no. 1, p. a004903, Jan 2012, doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a004903.

- O. Chaudhuri, J. Cooper-White, P. A. Janmey, D. J. Mooney, and V. B. Shenoy, “Effects of extracellular matrix viscoelasticity on cellular behaviour,” (in eng), Nature, vol. 584, no. 7822, pp. 535-546, 08 2020, doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2612-2.

- P. Martin and R. Nunan, “Cellular and molecular mechanisms of repair in acute and chronic wound healing,” (in eng), Br J Dermatol, vol. 173, no. 2, pp. 370-8, Aug 2015, doi: 10.1111/bjd.13954.

- M. Najafi, B. Farhood, and K. Mortezaee, “Extracellular matrix (ECM) stiffness and degradation as cancer drivers,” (in eng), J Cell Biochem, vol. 120, no. 3, pp. 2782-2790, 03 2019, doi: 10.1002/jcb.27681.

- L. Nissinen and V. M. Kahari, “Matrix metalloproteinases in inflammation,” (in eng), Biochim Biophys Acta, vol. 1840, no. 8, pp. 2571-80, Aug 2014, doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.03.007.

Discover more from Research Hive

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Manchester and the Immuno-Matrix”