By Katie Lowles

We have mouse research to thank for the development of breast cancer drugs which have treated and saved the lives of millions of patients around the world. We have research in rabbits and dogs to thank for the discovery of insulin and the subsequent purification technique, which has allowed type 1 diabetes patients to survive and manage their condition effectively since 1922. We have primates to thank for giving us important insights into AIDS pathogenesis, eventually leading to the development of therapies for the disease, meaning AIDS is no longer the untreatable death sentence it once was.

While almost everyone would agree that treating, curing and improving the quality of life of patients using medicine is a good thing, not everyone agrees that using animals to achieve this outcome is necessary or even ethical.

Organised opposition to the use of animals in research began in 1875, when the National Anti-Vivisection Society (NAVS) was founded. The body has funded non-animal scientific and medical research and works with legislators to support the replacement of animals in research with alternative methods. They have also exposed animal suffering during undercover investigations in laboratories. Similarly, People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) believes that no animals should ever be ‘exploited’ in any way, often using aggression or shock-tactics to spread their beliefs.

While supporters of PETA and other similar organisations hold the belief that using animals in research is simply wrong without exception, many research scientists hold a more utilitarian philosophy to justify the use of animals in research. Utilitarianism involves weighing up the harm and benefit of an action and if benefit > harm, an action is deemed justifiable and morally sound. However, it is not too difficult to see the flaws in both philosophies. If animal research doesn’t take place, we either forfeit certain advancements in science, for example no new medicines, or we test on humans instead. Neither of which seems a feasible, attractive nor even ethical solution. Conversely, a utilitarian belief ignores to which species benefit or harm is being done. For example, if 500 mice are sacrificed in a chemotherapy toxicology study, but the treatment goes on to save 5000 patients, it is easy to see that humans are benefitting hugely from a relatively ‘small’ loss of life. But of course, for humans it is only benefit, and for mice only harm – so does the seemingly simple utilitarian philosophy hold up?

Research in the UK involving animals has to comply with stringent rules and regulations and be approved by the Home Office, who will ensure that the benefit of conducting the research outweighs predicted harm done to the animal. Crucially, animal research in the UK must follow the principles of the 3Rs; Replacement, Reduction and Refinement.

- Replacement = avoiding or replacing the use of animals.

- Reduction = minimising the number of animals used during an experiment.

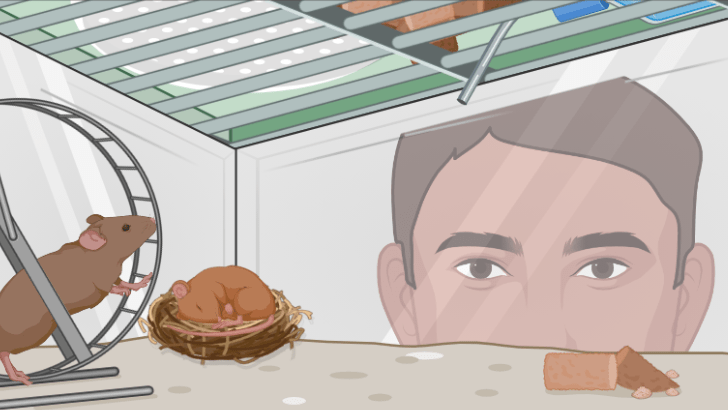

- Refinement = minimising animal suffering and promoting animal welfare.

The 3Rs are designed to be a framework upon which the most humane animal research can be conducted. The ideal scenario is ‘replacement’, which removes the need for animals altogether in an experiment. Instead, consenting human volunteers, in vitro techniques and mathematical and computer models are adopted. ‘Reduction’ means both reducing the total number of animals used in an experiment, but also maximising the information obtained from each animal used. For example, one lab may need mouse brains, while another uses legs, and so on. This requires organisation and communication between researchers. A more collaborative organisation is likely to follow the principle of reduction more effectively. Finally, ‘refinement’ refers to practices that maximise the welfare of the animals, for example improving their housing and husbandry techniques. It also involves planning experiments meticulously to reduce suffering, pain and discomfort in animals. Refinement is also crucial for ensuring the validity of data obtained from animals. Animals have strong homeostatic mechanisms, so incorrect housing or husbandry can lead to compensatory physiological and behavioural changes. Similarly, pain and suffering in animals can alter an animal’s physiology and even immunology, calling into question the robustness of any results collected.

In March 2020, an opinion poll carried out for the Understanding Animal Research organisation showed that 75% of people asked accepted the use of animals in research as long as there was no unnecessary suffering to the animals and no alternative. Unfortunately, bad animal research practices do happen, where the 3Rs are not followed. Laboratories have been shut down due to animal mistreatment and negligence. Quite rightly, this often makes the news and fuels the fire in those who believe researching on animals is wrong. It also lets down the overwhelming majority of researchers who truly care for the welfare of their animals. Perhaps a way to overcome this is for institutes with animal units to adopt a truly transparent and honest relationship with the general public. Writing reports on animal care in the facilities and even giving tours to those interested could help to bridge the knowledge gap between the public and the scientist.

This honest relationship could also benefit the researcher and animals themselves; the more open we are encouraged to be, the more we have to scrutinize and challenge any work involving animals, leading to even better practices.

Thankfully, the use of animals in research is decreasing year upon year as in silico methods become more powerful. Until technology advances to a point where we can model everything without the use of animals, we should be encouraged regularly to question why we are using animals, if it is necessary and to be grateful for the advancements in science that they have enabled.

Discover more from Research Hive

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Animals in Research”