By Chloe Brady

Throughout pregnancy, the fetus (consisting of both maternal and paternal genes), must evade the maternal immune system. For this reason, the fetus has been previously described as the most successful organ transplant, tolerated by the mother for around 40 weeks. In the 1950s, biologist Sir Peter Medawar first recognised that pregnancy is a ‘paradox’ where the fetus can survive, despite being 50% genetically foreign to the mother1. Medawar hypothesised that the mother and fetus must therefore have specific adaptations to sustain healthy pregnancy. Since this time, much research has focused on the placenta (or afterbirth), as it is the organ where fetal cells encounter maternal blood and therefore is essential in helping to develop maternal-fetal tolerance.

The human placenta: structure and function

Though often overlooked, the placenta is vital for providing oxygen and nutrients to the developing fetus, and acts as a transport system for the removal of waste via the mother’s circulation. Early in pregnancy, cells from the fertilised embryo invade and remodel the mother’s arteries to establish a connection between maternal blood and fetal cells. Within the developed placenta (Fig. 1), fetal blood vessels, or villi, branch from the umbilical cord into the intervillous space. Maternal blood in the intervillous space bathes the villi and is in contact with specialised cells known as trophoblasts which allow transport of substances to and from the fetus. The trophoblast layer consists of two cell types: the syncytiotrophoblast on the surface, and a layer of cytotrophoblast underneath which fuse together to continuously regenerate the syncytiotrophoblast. As the syncytiotrophoblast are in contact with maternal blood, this site is commonly referred to as the ‘maternal-fetal interface’2.

Trophoblast adaptations

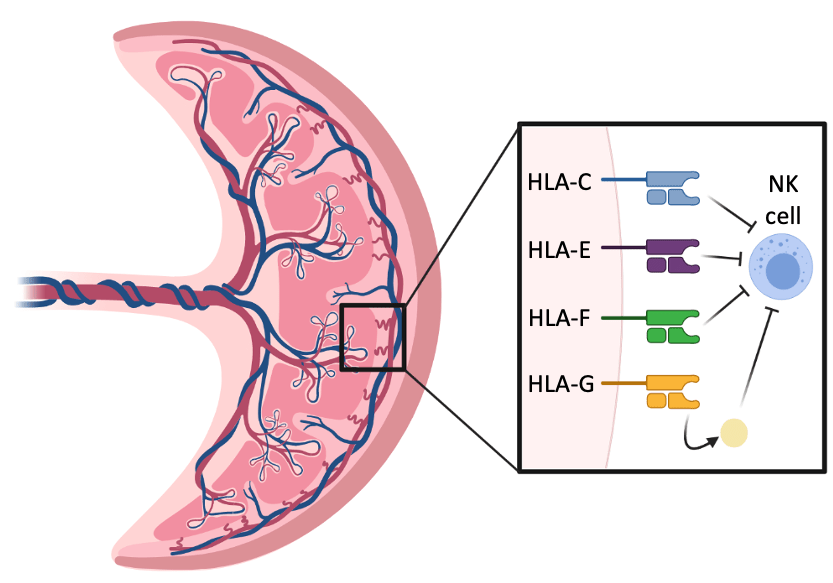

As the trophoblast are in direct contact with the maternal blood and therefore maternal immune cells, they have evolved several mechanisms which prevent them from mounting an inflammatory response. Arguably the most important and well recognised is their unique expression of molecules known as human leukocyte antigen (HLA). HLA is expressed on every cell within the body and acts as a signal which allows the immune system to recognise pathogens and what is ‘self’ or ‘non-self’. To allow humans to fight off a broad range of pathogens, HLA alleles vary widely between individuals. This causes problems in organ transplantation as exposure to non-self HLA results in a strong immune response and rejection of the graft. As the fetus is 50% genetically different to the mother, the foreign HLA inherited from the father should normally cause a non-self-response and inflammation leading to cell death. However, trophoblast cells express specialised HLA which interact with maternal immune cells and regulate their function (Fig. 2).

HLA currently identified on the surface of trophoblast include HLA-C, E, F and G3. All of these have been shown to inhibit the action of natural killer cells which are the most abundant immune cell type within the pregnant uterus. HLA-G is also secreted as a soluble form. In addition, trophoblast downregulate other HLA with high genetic variability and therefore further reduce their risk of recognition by immune cells. Despite the importance of HLA in pregnancy, many of their functions remain unknown and therefore are a particular current research focus in reproductive immunology. Alongside HLA, trophoblast also express many other molecules on their surface which regulate maternal immune cell function. Importantly, maternal immune cells must retain some of their inflammatory capabilities to defend mother and fetus against infection. These cells within the pregnant uterus therefore have adaptations and roles to support pregnancy compared to others circulating the rest of the body.

The maternal immune response

Immune tolerance during pregnancy can be described as a reciprocal process, relying on both the trophoblast and maternal immune cells to sustain the fetus. Figure 3 shows the interactions between both maternal immune cells and the trophoblast which promote tolerance towards the foreign fetus. Trophoblast cells release various cytokines including interleukin-10 (IL-10), which create an anti-inflammatory environment. IL-10 stimulates the induction of regulatory T cells (Tregs), which in turn inhibit cytotoxic T cells and prevent rejection of fetal cells. Dendritic cells, which normally present foreign antigens to immune cells, are silenced within the uterus and instead of being pro-inflammatory induce more Tregs. Throughout pregnancy, cell turnover by the trophoblast can release cell contents into maternal blood, and macrophages play an important role in soaking up this debris to prevent recognition by maternal inflammatory cells4.

Why is immune tolerance in pregnancy so interesting?

For the immune system, pregnancy is a unique state where inflammation to fight off pathogens must be balanced with tolerance to allow the fetus to grow and survive. There is growing evidence to suggest that several conditions including infertility, miscarriage, stillbirth and pre-eclampsia may be caused when this balance is disturbed5. In addition, inflammation towards the fetus during life in the womb may have more long-lasting effects such as neurological disorder6. As many adaptations of the immune system during pregnancy remain poorly understood, it is likely that further research may allow therapies which modulate the immune system to be utilised to reduce pregnancy loss and improve infant health.

References

1. Medawar, P. Some immunological and endocrinological problems raised by the evolution of viviparity in vertebrates. Symp Soc Exp Biol 7, 320–338 (1953).

All figures created with BioRender.com

Discover more from Research Hive

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.