Author: Katie Lowles // Editor: Erin Pallott

PhD researchers from the University of Manchester (Katie Lowles, Hannah Tompkins and Will Zammit) are teaming up with Manchester’s SHE choir, an inclusive choir for women and non-binary adults, to deliver a talk and singing session at Bluedot festival this summer.

This blog was written for members of the audience at Bluedot (the music and science festival held at Jodrell Bank), as well as any Research Hive readers who wish to learn more about lungs, immunology and why car sing-alongs and belting out tunes in the shower may be improving your lung health and overall wellbeing!

What Do Our Lungs Do?

While many of our organs can make a good argument for being the most important and vital part of our body, the lungs are definitely a good contender for top position. Our lungs allow us to absorb oxygen from the air we breathe in and pass it into the bloodstream, meaning it can be distributed around our body, which is essential for our cells to function. At the same time, carbon dioxide, which is produced as a by-product of respiration, diffuses from our bloodstream and into our lungs where it is expelled as we breathe out. This process is called gas exchange.

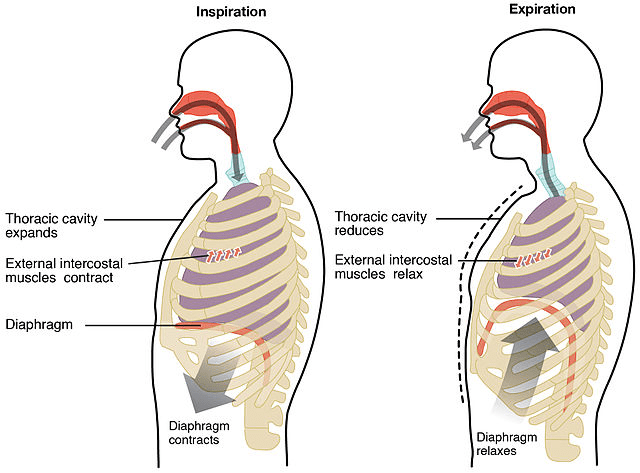

If you have healthy, functioning lungs, you probably don’t even think about breathing. However, your main lung muscle, the diaphragm, is actually doing some pretty heavy work. The diaphragm is a dome-shaped muscle situated underneath the lungs. As you inhale, your diaphragm contracts – flattening the dome – creating space for air to enter. When you exhale, the diaphragm relaxes and the dome shape returns.

There are two other respiratory muscle groups that help with breathing: The rib cage muscles and the abdominals, or abs. The stronger these muscle groups are, the more efficient your breathing will be. You don’t need abs of steel or a six-pack to improve your respiratory health; these muscles can be strengthened by breathing exercises and physical exercise like walking and running.

Law Enforcement Lungs

Of course, the air we breathe in isn’t always clean. It contains pollutants, bacteria, allergens, and virus particles. With the lungs being an interface between the outside world and our body, our immune system must deploy protective mechanisms to stop harmful substances entering our body and making us ill.

The immune system can be split in two arms: innate and adaptive immunity.

The innate immune system is quick to respond to harmful substances, but it is non-specific. Cells involved in innate immunity can be likened to the police. They are first on the scene and provide general defence against harmful substances, but these cells lack special training and can be easily overwhelmed. Cell types of the innate immune system include:

- Phagocytes: A bit like Pac-men; they identify and engulf harmful substances.

- Natural killer cells: Like their name suggests: they kill foreign substances quickly.

The adaptive immune system is slower to respond but it is specific for the target. Similar to the Special Forces, who are specially trained to deal with specific potentially harmful situations; the immune cells of the adaptive immune system are targeted to the exact infection type.

Cell types of the adaptive immune system include:

- T cells: Discriminate between healthy and abnormal cells. Express specific receptors for many different types of cells. They can kill or assist in the killing of potentially harmful cells.

- B cells: Create antibodies, which are proteins that bind to antigens on pathogens or to foreign substances, such as toxins, to neutralise them.

During the pandemic, you probably heard lots about antibodies. They are Y-shaped molecules which specifically capture targets to aid their elimination. Antibodies are essential in recurrent infection. Once our body has produced antibodies for an initial infection, it is equipped to quickly produce more if we are ever infected again in the future by the same pathogen. This is why a second infection is usually less severe than the first, as the harmful substance is being removed quickly thanks to antibodies.

What Happens When Your Lungs Are Unhealthy?

In an ideal world, harmful substances are removed so efficiently by our immune system that we don’t even realise we’ve been exposed to them. However, some individuals have a weakened immune system, which prevents them responding appropriately to harmful substances. Examples of this are patients with COPD, asthma, and lung cancer.

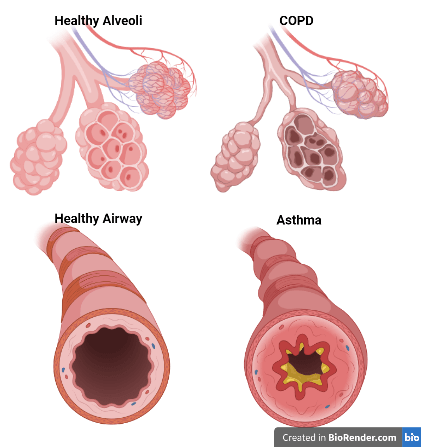

Asthma

Asthma is an example of an acute condition; a condition that comes on rapidly but gets better quickly after treatment. When people have asthma attacks, they are generally short-lived bouts of wheezing and breathlessness. During an asthma attack, the lung airways narrow and may produce extra mucus. This makes breathing difficult as there is not enough space for efficient gas exchange to take place.

You’re more likely to develop asthma if it’s in your close family, such as your parents or brothers and sisters. This is partly down to genetics and partly down to the shared environment you live and grow up in. For some people, asthma is a minor nuisance, making it hard to play sport or do tough physical activities. However, in severe cases, it can make it hard for people to undertake normal day-to-day tasks, affecting their quality of life and even shortening their life span.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

Unlike asthma, COPD is a chronic condition. Chronic conditions are persistent and long-lasting, requiring ongoing medical attention and cases often get progressively worse over time. You may also know COPD as emphysema or chronic bronchitis. Generally, COPD is a gradual decline of lung function. People with COPD often find it hard to breathe as the alveoli (air sacs) in their lungs become damaged, meaning gas exchange is very inefficient.

Whether you have an existing lung condition or not, it is important to keep your lungs as healthy as possible. Of course, there are the obvious things you should do: Regular physical exercise, avoid smoking/vaping, and avoid exposure to indoor and outdoor pollutants that can damage lungs.

Sing Yourself Happy (And Healthy)

If you’ve ever sung your favourite song in the shower or belted out some sing-a-long tunes on a long car journey, you’ll know that singing has mood-boosting effects. In fact, feel-good brain chemicals including endorphins, dopamine and serotonin are released when you sing, and evidence shows that stress hormones are also suppressed as you sing. The best part is that singing will make you feel happier regardless of whether you can hold a tune or not!

What you may not know is that singing can be as good for us physically as it is mentally. A study has shown that the physical effort of singing while standing up is equivalent to a walking at a moderately brisk pace. When we sing, our respiratory muscles must work hard to get enough air in to our lungs while also allowing us to project our voice. Singing helps to train our respiratory muscles and strengthen them, resulting in improved diaphragm control and the ability to take deeper breaths.

People with respiratory conditions shouldn’t be put off from singing as studies have shown that signing can have a positive impact on the lives of people with lung disease. Gradually building up stronger respiratory muscles can reduce breathlessness, help people feel more in control of their own breathing and even help people to manage their condition better. Asthma + Lung UK holds ‘Singing for Lung Health’ sessions in towns and cities up and down the UK. Have a look at their website for further information or to find your nearest group.

Discover more from Research Hive

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.