Author: Rebecca Light // Editor: Erin Pallott

In an age where information about any subject is available at the click of a button, we have all been exposed to ‘#antivax’ information on social media, whether that be someone on a community Facebook page showing genuine concern over the side effects of the COVID-19 vaccine they read from unreliable sources (misinformation), or an anonymous X user intentionally spreading false information and recruiting others to their cause (disinformation). Facebook members may reach out to fellow users with anti-vaccination ideas, purely for the aim of discussing what is true and what is false, to reach conclusions about whether to be vaccinated or not. On the other hand, social media members, such as some “wellness influencers”, may promote anti-vaccine ideas with the intention of selling a product and profiting from the spread of disinformation. For example, Ingrid De La Mare Kenny, who has a significant Instagram presence, promotes her product ‘Simply Inulin’ which sells for €26.99 (£23.19) on her website. Advertised as a dietary supplement, the powder claims to give a “flatter tummy fast” (a problematic sentiment in itself). During the pandemic it also conveniently promised to boost the immune system and prevent COVID-19 infection. However, there is no evidence for this “immune-boosting” benefit; inulin is recognised by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as a dietary fibre, but its effects on preventing COVID-19 are unsubstantiated. This spread of anti-vaccination propaganda is hugely dangerous, as it increases hesitancy towards vaccines, and therefore diminishes the defences of herd immunity. To promote global health by increasing vaccine uptake for childhood and adult immunisations, such as MMR and annual flu jabs respectively, we must understand vaccine hesitancy in order to target it.

What is vaccine hesitancy?

Through my work on my Final Year Research Project entitled ‘Vaccine Hesitancy and Trust in the Public: An MMR Case Study’, I discovered the ‘5C model’ of vaccine hesitancy. This means that, at an individual level, there are five drivers of vaccine hesitancy: confidence, complacency, constraints, risk calculation, and collective responsibility. Together these encompass the idea that vaccine hesitancy builds from people’s own perspectives towards vaccines, shaped by their own experiences, discussion with peers, and knowledge of the public health effect. Broken down, this encompasses someone’s beliefs that the vaccine may not work (confidence), their feeling that the vaccine is not necessary for them (complacency), their ideas that they are not physically ‘able’ to get the vaccine (constraints), their opinion that the vaccine will do more damage than good (risk calculations), and their lack of a need to contribute to public health (collective responsibility). Much of the information that people use to form their ideas comes from social media, and they are then solely responsible for choosing to believe that information, or seeking further clarification before they follow the advice.

Types of vaccine information on social media

Positive, pro-vaccine information is easy to find on social media, such as the #DoctorsSpeakUp event on Twitter (now X) in March 2020, where medical professionals were encouraged to show support towards vaccines. The aim here was for knowledgeable healthcare professionals to promote vaccines to a community where anti-vaccine information is rife; however, the event was hijacked by those wishing to express their opposition of vaccines. Out of 847 tweets, just under 20% were shown to express pro-vaccination attitudes, and almost 80% of tweets expressed anti-vaccination beliefs, using the hashtag as a way of conveying their disappointment that doctors were not agreeing with their sentiments.

In addition, the purposeful spread of vaccine misinformation occurs on a regular basis. For example, anonymous accounts on X collating vaccine conspiracy information and reposting it for their large audiences, creating a community where these toxic beliefs can be shared globally, and can spiral out of control. For people who use TikTok more frequently, the so-called “crunchy mum” trend presents a veiled avenue of vaccine communication, expressing anti-vaccination beliefs under the pretence of building a community of likeminded people, supporting each other through the trials of motherhood. Whilst this is not so aggressively spreading conspiracy theories about vaccines (such as the “COVID-19 vaccine microchip”, injected to track and control the population), it introduces a different avenue of vaccine misinformation driving vaccine hesitancy; under the guise of support and comradery. Families are able to watch these videos and enter into the ‘comforting’ community, engage in anti-vaccine discussions, and therefore increase their beliefs that vaccines are not necessary, or even harmful, for them or their children. Through the use of meaningful and connective themes of family, religion, and homemaking, mothers are able to utilise social media and monetise off of objectively ‘aesthetically pleasing’ content.

How can we combat the spread of vaccine misinformation?

One of the best ways to minimise the effects of vaccine misinformation is through effective, accurate science communication that anyone can understand, using avenues such as Research Hive! By distributing pro-vaccine information from people well-versed in the science field, members of the public are able to educate themselves on the truth behind vaccines, enabling them to make informed decisions about their vaccination status. Scientific researchers should be encouraged to actively engage in conversations with the public, both on and offline. Linking this with pro-vaccine discussions between friends and with healthcare professionals would allow positive information surrounding vaccines to be more broadly distributed, potentially leading to a point where pro-vaccine beliefs outweigh anti-vaccine beliefs.

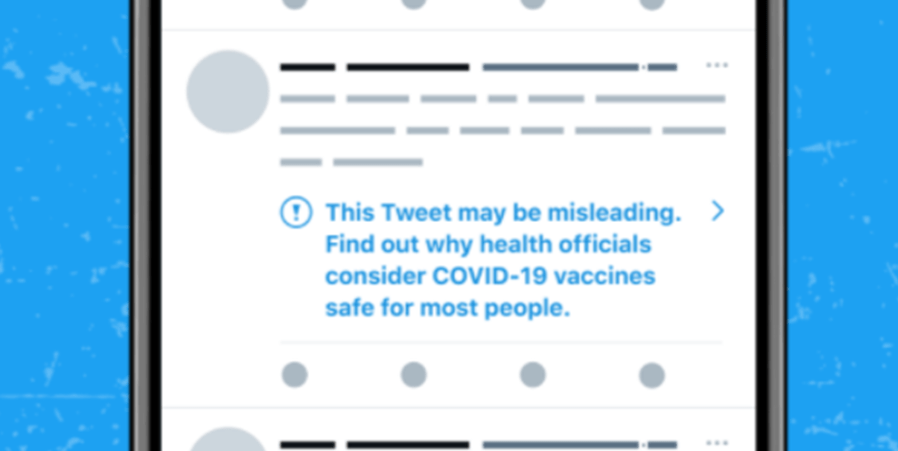

In addition, studies have shown that using fact-checking labels on X posts leads to a decrease in conspiracy beliefs surrounding the MMR vaccine and engagement with MMR vaccine misinformation. Despite this decrease not being statistically significant, this remains a vital method of decreasing vaccine hesitancy that, combined with alternative methods, could have a large impact on global vaccine uptake.

As we see new social media platforms continue to develop, it is vital that we consider how vaccine information will be portrayed on these platforms. Methods of combatting vaccine mis- and disinformation should be employed from the point of posting, and pro-vaccine information should be readily distributed globally. By fighting against the spread of misinformation and providing trustworthy information surrounding vaccines, we can target vaccine hesitancy that is becoming rife, with an aim to increase vaccine uptake for childhood and adult immunisations and promote the health of the global population. As novel diseases emerge, as with the COVID-19 pandemic, the importance of vaccines will continue to be disputed; therefore, scientists, policy makers, and the public must work in conjunction to spread as much positive factual vaccine information as possible.

Discover more from Research Hive

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

One thought on “Beyond the Screen: Understanding Vaccine Hesitancy in the Age of Social Media”