Author: Dr Victoria Verkerk // Editor: Cherene de Bruyn

Since the 1990s, virtual reality (VR) has literally transformed the tourism industry by enabling tourists to virtually travel anywhere, anytime without any limitations. VR offers unique opportunities for immersive experiences, allowing tourists to explore destinations and attractions from the comfort of their homes. For example, WildEarth, an online TV channel, allows people from anywhere in the world to virtually ‘partake’ in a safari trip in South Africa. During the COVID-19 pandemic, Google Keyword Planner recorded a significant rise in searches for the term “virtual tour,” highlighting the growing interest in VR. Notably, the late Queen Elizabeth herself utilised this technology, making her one of the first ‘virtual tourists’.

Despite its significant impact, scholars debate whether VR will ultimately substitute conventional tourism. However, I propose that VR should be considered a new niche within the tourism industry. VR is a fascinating topic because I like to focus on technology and its impact on tourism. My fascination with technology’s influence on tourism drives my research at the University of Pretoria, South Africa, where I focused on VR’s potential to be recognised as a distinct niche within the sector.

1. What is Virtual Reality?

In 1989, Jaron Lanier, an American computer scientist and visual artist, coined the term “VR”. Many scholars agree that VR is a difficult and complex term. The definitions of virtual and reality are polar opposites of each other. The word ‘virtual’ means something that is imaginary or simulated, in other words fake, whereas ‘reality’ can be defined as something real and tangible, in other words not fake. It can be argued that VR takes the user from their reality and transports them to a 3D virtual world where they interact in real time. In terms of tourism, VR is defined as a non-physical form of tourism that allows tourists to travel to a computer-generated destination without them having to physically go there.

2. Virtual Reality in Tourism: The Benefits and Barriers

VR is one of the most innovative technologies to emerge in the tourism sector. The tourism industry is one of the first industries to embrace VR, initially in the form of flight simulations. Today VR plays a significant role in the tourism industry, especially in marketing and promoting sustainability. Traditional marketing tools, such as websites and brochures have become outdated and boring, often falling short of accurately representing destinations, which leads to disappointments. An example occurred in the 1990s when Las Vegas was marketed as a family-friendly destination, which was in contrast with its reputation as “Sin City”, leaving many families disappointed. It is for this reason that many scholars believe that VR is the ultimate marketing tool because it allows tourists to immerse themselves in the marketing campaign through the ‘try before buy’ approach. This enables potential travellers to explore a destination or attraction virtually before committing to a physical trip. For instance, tourists from the UK can experience an African sunset through VR during winter in the comfort of their warm houses. This might encourage them to visit South Africa for an actual safari. VR then has the potential to allow for a richer and more accurate representation of what to expect on a visit, ultimately improving satisfaction and driving tourism.

Many tourism destinations have suffered from vandalism and destruction by tourists. For example, in South Africa, visitors have chipped away at, drawn graffiti on, and splashed soft drinks on San rock art sites to make them more visible. Unfortunately, these actions are to the detriment of cultural heritage sites and the damage is often irreversible. At these sites, VR can be used as the ‘ultimate sustainable tool,’ because through its virtual environment, it can reduce the impact of tourism and the damage caused by large numbers of visitors to a site by providing a virtual alternative. With VR, tourists can enjoy, for example, rock art sites without physically being at the site. They can immerse themselves in the experience, virtually ‘touching’ and exploring the art in detail. This not only offers a rich, immersive way to engage with cultural heritage but also helps preserve the rock art and formations for future generations by reducing foot traffic and environmental impact.

On the other hand, some argue that VR poses a threat to tourism, especially when it comes to mental and physical health and technological limitations. One of the major concerns is the impact VR can have on people’s well-being. Physically, users can experience issues like cybersickness, similar to motion sickness. It occurs when there is a disconnect between what the eyes perceive in the virtual environment and the body’s actual physical state. A second impact is eye strain which is caused when users focus on a digital screen for a prolonged time. Additionally, VR can affect mental health by blurring the line between reality and fantasy, making it difficult for individuals to distinguish between virtual experiences and real-life events. The immersive nature of VR creates a sense of comfort, which may lead tourists to underestimate the risks and consequences of their actions. Furthermore, there are concerns that VR may lead to addiction, with some referring to it as “electronic LSD,” as users might become overly reliant on virtual experiences.

At the moment, the development and implementation of VR at heritage sites and attractions is limited by technological developments. For VR to function properly, its technology requires constant updates and maintenance, which could lead to the so-called digital divide due to the high costs involved. This financial burden means that only countries in the global North, such as the UK and the USA, can afford to invest in VR infrastructure, while countries in the global South, like South Africa and India, risk losing out on potential tourism revenue. Without the funds and resources to build VR experiences, what was meant to make attractions more inclusive could actually do the opposite. Instead of levelling the playing field, these disparities could exacerbate existing inequalities in the tourism sector, limiting access to immersive experiences for many potential travellers in less affluent regions.

3. The Virtual Substitute

The jury’s still out on whether VR can truly replace traditional tourism. There is potential for VR to effectively address several challenges associated with traditional tourism, such as visa requirements, overcrowding, and high costs. By allowing people to “travel” from the comfort of their own homes, VR offers an accessible escape for those who may not have the means or ability to travel in real life. VR captures many components of conventional tourism, offering immersive experiences that evoke feelings of adventure and exploration through visual and auditory stimuli.

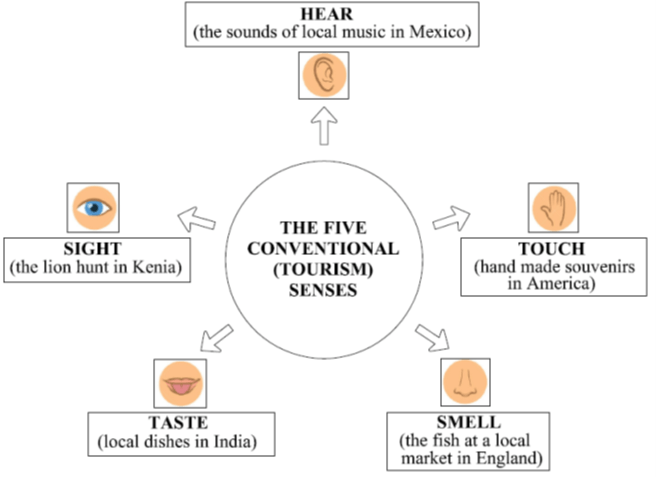

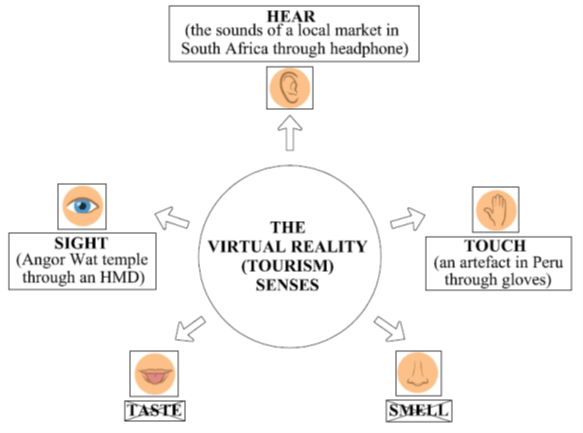

VR is often criticised in tourism because it is virtual and cannot fully replace the authentic sensory experiences offered by physical travel. Traditional tourism engages all five senses – sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell – creating a rich and authentic experience that VR currently cannot replicate. The inability of VR to simulate taste and smell is a significant limitation. Plus, travel is often a social activity where you interact with locals and meet fellow travellers. In contrast, VR experiences tend to be solitary, missing that social connection which adds to the emotional and transformative impact of travel. According to the United Nations World Tourism Organization, tourism involves some form of physical movement, which is another aspect VR does not replicate at the moment.

4. The Final Virtual Verdict: Substitute or Tourism Niche?

This is a complex debate, but in my view, VR should not be seen as a replacement for traditional tourism. Instead, it has the potential to carve out its own unique niche within the travel industry. One key reason for this perspective is that VR enhances the tourist experience, particularly in terms of marketing and sustainability. VR tourism has its own growing audience, especially among tech-savvy Millennials and Generation Z. What makes VR even more exciting is its ability to offer a wide range of experiences, including drone tourism, e-tourism, film and TV tourism, gamified travel experiences, smartphone and app-based tourism, space tourism, and even virtual tours with 360° images and videos. This diversity highlights VR’s potential to complement traditional travel experiences rather than replace them.

For VR to be recognised as a viable niche in tourism, several significant challenges must be addressed. One of the most pressing issues is the digital divide between the global North and South. Many countries in the global South lack the financial resources to invest in VR technology, which means they miss out on opportunities to attract tourists through this medium.

Another challenge is the perception that VR experiences are inauthentic. Since VR struggles to engage all five senses—particularly taste and smell—many people are sceptical about its ability to match the richness of traditional travel. Overcoming the barriers to VR tourism is essential for gaining wider acceptance of this niche within the travel industry. Looking ahead, VR has the potential to establish itself as a recognised niche in tourism, offering innovative ways to explore the world.

About the Author

Dr. Victoria Verkerk earned her PhD. in Heritage and Cultural Tourism in 2022 from the University of Pretoria, South Africa. Her research covers a broad spectrum of topics within the field of tourism, including pink tourism, archaeological tourism, and virtual reality tourism. She has published two articles in peer-reviewed tourism journals and contributed to Luxiders’ feature titled “Virtual Tourism: The Sustainable Way to See the World”. Additionally, she has presented the findings of her research at academic tourism conferences, including the ATLAS Africa Conference, ENTER22 e-Tourism Conference, and MTCON Conference. She has also served as a reviewer for several tourism journals, including Tourism and Hospitality Management, Tourism Review, International Journal of Tourism Research, and Tourism Critiques: Practice and Theory.

Discover more from Research Hive

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.