Author: Rashmi Danwaththa Liyanage // Editor: Erin Pallott

A Mother’s Journey

I woke up in the gloom and I could see some black and white pigeons huddled together on a neighbour’s roof embracing the warmth and serenity, a sheer contrast to my inner disarray. Just days after the Southport tragedy, and riots occurred a few miles away from our home, police sirens and helicopter blades sliced through our usually quiet suburb. As a brown-skinned mother, I watched my five-year-old son press his face against the window, eager to join his white friends in the park. His innocent curiosity only deepens my inner turmoil. He asks questions about the world around him and the painful loss of three little lives that echoed through news, neighbours and our community. I found myself at a loss for words, struggling to express my grief and fear in words that a child could understand.

“Amma (Mummy in Sinhalese), what’s happening around? Why so many helicopters? Why can’t I go play today?” he asks. “And why is our skin brown when my friends’ is white?”

His questions hover between two realms – Sri Lanka of our ancestry and our life here in Britain. As a Sri Lankan Sinhala British woman, I carry a paradox; in my homeland, I belonged to the majority, but here I navigate myself as a minority. The irony doesn’t end here! Our daily life is a battle between cultures. While I long for the spicy comfort of rice and curry, my son begs for fish and chips! He speaks English with a British accent, while I catch myself thinking in Sinhalese. These small moments mirror our larger struggle, where do we truly belong? This question of belonging isn’t just personal, it’s become the heart of my academic journey. A blessing in disguise! My PhD research examines how discrimination and social identity may trigger psychosis among ethnic minorities in the UK. It’s more than just a research project, it’s my attempt to understand our shared experience of straddling two worlds. Through each interview and survey and every piece of data, I’m not just seeking academic answers, I’m searching for pieces of myself, of my son’s future, of our true place and identity in this complex British tapestry.

Cries of exclusion: Changing mental landscape?

Have you ever got a feeling that your mind playing tricks on you, you’re seeing things differently from what others see or believing in things that don’t exist? This is a possible symptom of Psychosis, a severe mental health condition with combined symptoms including hallucinations and delusions. Typically, 1.5% to 18.6% of the general population in the UK could be suffering from subclinical paranoia, where symptoms have not reached the threshold of a clinical diagnosis. But here’s something troubling: In the UK, individuals from ethnic minority backgrounds are more likely to experience psychosis than our White British counterparts. For instance, if you’re African-Caribbean, you’re seven times more likely to experience psychosis. If you are Black African, the risk is four times higher and if you are Asian, you have a three times higher risk of developing psychosis compared to our White counterparts. This is not just a statistic, but echoes of genuine struggle of real people.

There has always been a debate over the genesis of psychosis, whether it is genetically, biologically or socially driven. Does our social experience and belonging play a vital role in the development of psychosis? Evidence shows that Black communities have the highest reported rates of psychosis in the UK compared to their country of origin. Our mental health is similar to the life cycle of a plant; of course, the genetics of a seed undoubtedly is important in germination yet, external factors such as the quality of soil, weather conditions and the presence of harsh chemicals equally impact the growth of a plant. Unlike our genetics, the external factors could actively be altered and improved for better outcomes. Considering different living conditions and different social exposure of human beings, the emerging trends certainly convey that health and wellbeing cannot be explained by the biology and genetics alone. It is evident that experiences of lack of belonging, exclusions, and discrimination can leave the deepest marks in our minds.

My endeavour to understand these social phenomena is not only an academic gain, but an avenue to help and heal people like us going through similar struggles while preventing others from experiencing them. It is, therefore, seeking answers to this hard question: How does the feeling of not belonging shape our mind?

Psychosis as a defence response

Recent studies on psychosis reveal a more troubling truth. The prevalence of psychosis is much higher in regions farther away from the equator while individuals with deeper skin tones are more likely to experience psychotic symptoms. The incidence of psychosis is also higher in developed countries compared to developing nations, while patients in developing countries often demonstrate better outcomes with greater responses to treatment. Evidence indicates that schizophrenia, the most prevalent psychotic condition, was either absent or very rare among hunter-gatherer populations and individuals with traditional lifestyles. This suggests a different story around the causes of psychosis; it is not merely the biology, but the social lens depicting different pictures over its onset. The prolonged exposure to social stresses may have a significant impact on the development and maintenance of psychotic conditions. While our research does not discount the biological factors over the genesis of psychosis, in this attempt we seek the influences of social premises such as discrimination, marginalisation and identity crisis. These conditions could be modified through behavioural changes, interventions, and policy procedures, in a way the biological influences cannot address.

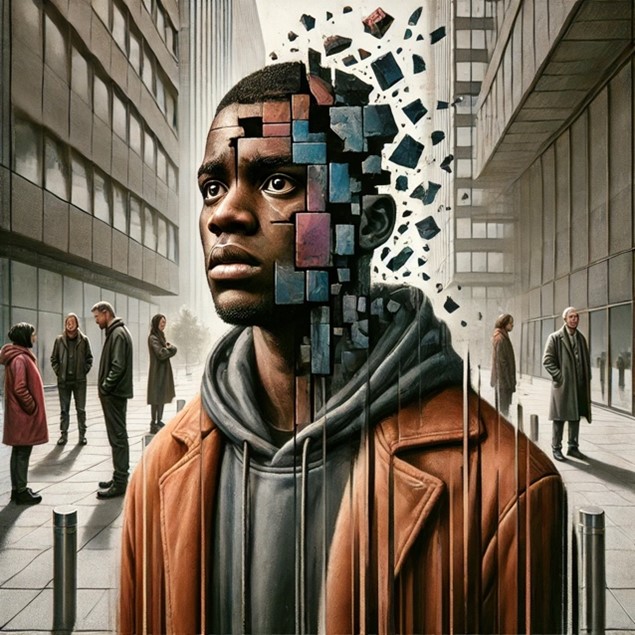

In some literature, psychosis is not merely an illness, but an adaptation phenomenon that serves as a defence mechanism, protecting individuals from external factors that overwhelm them beyond their capacity to cope. Being socially disconnected or lacking a sense of belonging may trigger defensive mechanisms to survive in this novel situation. Think you moved to a new country and constantly experience social exclusions. This is where your mind begins to play tricks, which we call paranoid delusions; a story your mind creates thinking the neighbourhood is conspiring against you.

Us vs Them

We humans are social animals, born to belong. Intergroup contact plays a crucial role in sociality, showing social connectedness protects us against physical and psychological stresses. Underpinning social coalitions offer significant buffering effects against physiological and psychosocial threats and stresses. Research on the Social Cure argues that increased social identity, characterised by a sense of belonging and group membership is vital for psychological wellbeing. Tajfel and Turner (1979) explained that a sense of identity is shaped through three interconnected psychological mechanisms. Self-identification: The feeling of which you feel emotionally connected to a group. Social identification: How you align yourself with the others within the group. You feel compatible and worthy. Social comparison: How you evaluate and compare your group against others, often seeing your group more favourably while other groups as inferior. In other words, our sense of ‘us’ versus ‘them’ shapes how we view and treat people within groups compared to out groups. People who feel a greater sense of belonging to larger social networks often experience greater health benefits, including lower risks of disease and death. If you are a White English, you identify yourself as a member of the majority, you then would recognise shared practices, and similar ways of speaking (where you call it typical English). You feel belonging, a comforting feeling that fosters pride. That’s where you would begin to view differences through a lens of hierarchy; comparing your group with other groups (i.e. Asian/African) where your practices are viewed as the standard, proper or civilised… compared to those of others!

The notion of Social Curse, on the other hand, could have a reverse impact on your mental health. The negative contact is stronger and more dominant than the impact of a positive contact. In other words, a thousand good deeds you do can be overshadowed by your one mistake! This impact extends far beyond just people directly involved but leads to broader prejudice and discrimination against the entire group like rippling waves from a fallen stone in a lake. If you are Black or Brown, you could be constantly overlooked, and your mistakes could be disproportionately criticised. You would feel weak and ostracised. This rejection therefore can lead to damaging effects on mental health and well-being.

Redefining home: Where does our heart truly rest?

As a first-generation migrant, I carry two homes within me, as a bird nesting in different seasons. Yet, I dread for my son, born under the British skies. My project has of course a long way to go, yet our preliminary research findings whisper a troubling truth; ethnic minorities in the UK experience more symptoms of psychosis than our White British neighbours. These numbers aren’t just statistics – they’re echoes of displacement, of interrupted belonging, the story of me and the future of my son.

Yet there’s still hope. We all seek unity through a rich culture of food, literature and countless other shared expressions. Our British streets come alive with the scent of curry, while Rushdie’s words mumble on British tongues alongside Shakespeare’s. Similarly, Bhangra and Reggae beats evoke the gentle moves of all ethnicities creating new rhythms of belonging. We together can write a new story of home, page by page, beat by beat.

Our paradox is we’re both strangers and natives, us and them, outsiders, and insiders, different yet the same. Like a tapestry woven from many colourful threads, our strength lies in our diversity. What we need isn’t just tolerance – it’s acceptance. Not just coexistence, but celebration. After all, we beg nothing costly, no treasures but something precious, a place to belong…

About the Author

I’m Rashmi Liyanage, a Sri Lankan British second-year PhD student in Psychology at Liverpool John Moores University. I’m also a mom, a wife and only daughter to my parents still living in Sri Lanka. My research focuses on intersections of discrimination, social identity, and psychosis among ethnic minorities in the UK. As an ethnic minority researcher myself, I’m deeply passionate about mental health issues affecting marginalised groups in the UK.

Discover more from Research Hive

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I wish you success with the research. What you had identified and highlighted are a prevailing delimma that cut across the world, when you are identified as a minority. It’s a challenge that an individual has to deal that issue.

LikeLike