Author: Emily Barrett // Editors: Federica Spaggiari and Sophie Alshukri

What does the word ‘radiation’ make you think of? In physics, the definition is broad: Any kind of emission of energy as electromagnetic waves or moving particles, including the light we use to see. But for many people, ‘radiation’ is synonymous with ionising radiation, with its distinctive yellow warning logo. Radiation is ‘ionising’ if it has enough energy to knock an electron, a tiny negatively charged particle, off an atom and form an ion, which means the atom now has a net electric charge. In doing so, the radiation can damage cells and DNA – which can increase the risk of cancer.

Paradoxically, the very properties that make ionising radiation dangerous also make it a powerful tool to fight cancer. In radiotherapy, radiation is harnessed to kill cancer cells by damaging their DNA and activating mechanisms of cell death, and ultimately shrinking or even eliminating the tumour. But it’s a fine balance: The goal of radiotherapy is to kill tumour cells without damaging the healthy tissue nearby. This is the focus of a lot of radiotherapy research, where the aim is to reduce side effects by making treatments more precise. When it comes to this goal, not all radiation is created equal – charged particles like protons have a natural advantage.

RADIATION AND MATTER

To understand why protons have an advantage in radiotherapy, let’s first take a detour into physics. Most radiotherapy treatments use X-ray photons, which are particles of light (a strange concept in itself) without charge or mass. By contrast, protons – small particles found in the nucleus of atoms – have mass and are positively charged. This means they interact with matter very differently.

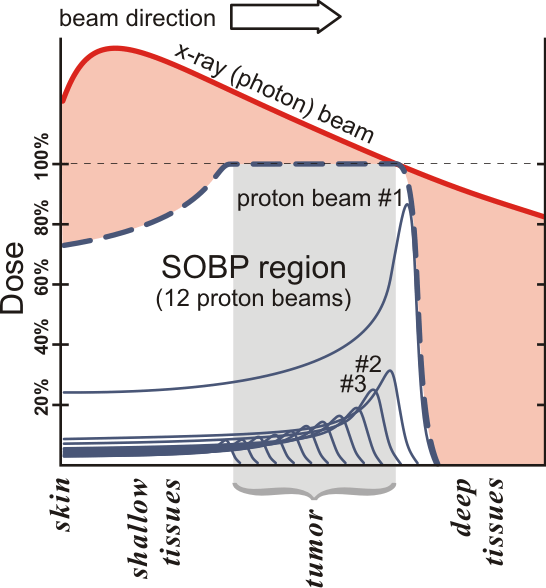

For one, protons slow down as they pass through matter and eventually come to a stop. As they stop, they deposit most of their energy. The ‘stopping distance’ of a proton beam in matter is related to its initial energy, so the energy of a proton beam can be chosen according to how deep the tumour is. This isn’t the same for X-rays, as the picture below shows – the intensity of a beam of X-rays decreases as it passes through tissue, but the beam doesn’t stop completely.

This isn’t to say X-ray treatments can’t be shaped to the tumour. In modern X-ray radiotherapy, techniques such as intensity modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) are used, where the radiation beam is shaped using an external device. But with proton therapy, an exit dose beyond the tumour can be avoided. This makes proton therapy particularly well-suited to cases where a critical organ is close to the tumour – such as head and neck cancers – or for treating children whose bodies are still developing. In cases like this, minimising the radiation dose to healthy tissue is especially crucial.

WHAT’S THE CATCH?

Of course, it isn’t just as simple as choosing the best kind of radiation for the job. One major drawback of proton therapy is the cost. Delivering clinical proton beams requires accelerating protons to speeds around 60% of the speed of light – it’s hard to comprehend just how fast this is. This requires expensive equipment, which costs more and takes up more space than the equipment used for traditional X-ray radiotherapy.

This is in a world where many countries do not have adequate access to radiotherapy and medical imaging machines, let alone proton therapy. According to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), while nearly all patients have access to radiotherapy in high-income countries, this drops to 60% of patients in middle-income countries and just 10% in low-income countries.

This problem of accessibility is further complicated by different countries’ varying approaches to healthcare. In the US, where healthcare is increasingly treated as a commodity, there are over 40 proton therapy centres (more than any other country worldwide), but extremely high healthcare costs mean not everybody has access to the same level of cancer care. The American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network (ACS CAN) found that nearly half of the cancer patients and survivors they surveyed have had cancer-related medical debt. This same survey found that those with debt are more likely to be behind on screenings or to delay care.

RAYS OF HOPE

It seems that these are twin objectives for the future of radiotherapy: to improve the quality of treatments through research and clinical trials, but also to improve access to radiotherapy. In spite of high costs, proton therapy is becoming more common. The UK once sent patients who might benefit from proton therapy abroad for treatments, but the past seven years have seen the NHS open two proton therapy facilities – one at the Christie in Manchester and one at UCLH in London. Making proton therapy more affordable and accessible is also a dedicated area of research. Innovative solutions like treating patients in an upright position, instead of lying down, can, in fact, cut down on equipment costs.

But solutions like this are far from being widely implemented. Meanwhile, proton therapy is still not an accessible treatment for everyone, especially not in low- and middle-income countries, which face a disproportionate cancer burden. The IAEA’s ‘Rays of Hope’ initiative was launched in 2022 with the aim of providing equipment and training to professionals to improve access to radiotherapy in lower-income countries.

This work, in tandem with research and innovation, can begin to chip away at the global disparities when it comes to access to cancer treatment. No medical research exists in a vacuum; proton therapy is an effective tool, but on this worldwide scale, it is just one part of a varied toolbox.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Hi, I’m Emily! I’m a PhD student in medical physics at the University of Manchester, researching proton beam therapy. I love to write about various areas of science – outside of my background in physics, I really enjoy reading and learning about nature and the environment. Connect with me on LinkedIn!

Discover more from Research Hive

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.