Author: Nina Wycech // Editor: Nithya Eswaran

I take my coffee black, my whisky neat – Hozier and I have that in common. Not everyone would agree with us, for some, this is madness. Why can’t some people handle the bitter taste of coffee, whisky or tonic water? The sensitivity to bitter flavour is genetically encoded and highly varies between individuals, more so than for sour, sweet or umami.

Today, the ability to taste bitterness influences our food preferences, but that was not always the case. Throughout evolution, bitterness has been a crucial part of our sensory palette. Many plant toxins taste bitter, and a sensitivity to their flavour evolved as an early-detection mechanism to protect us from poisoning.

But what is bitter is not always harmful, sometimes it is even a necessity. That truth is preserved in our language: “a bitter pill to swallow” is something unpleasant that has to be accepted. In that context, I like the saying we commonly use in Poland – “bitter medicine heals best”. Its equivalent is a Scottish proverb, though I believe it is seldom used: “bitter pills may have blessed effects”. Having drunk wormwood for an upset stomach, I whole-heartedly agree. It is both the most effective thing I tried and the worst tasting one.

Happy Accident

Like many things in science, the discovery of the variability of bitter taste perception was a result of chance. Almost a hundred years ago, in times when researchers had more freedom in their investigations, Dr. A.L. Fox was investigating a substance called, in short, PTC (phenylthiocarbamide), structurally similar to glucosinolates from food like brussels sprouts or cauliflower. As some of PTC’s particles flew into air, him and his coworker had a strikingly different sensory experience of it. So, they did what any reasonable researcher would do at that time – they tasted it. Dr Fox tasted nothing, Dr Noller noted it was “extremely bitter”. There appeared a question – why does it taste differently for them and how common each variant might be?

The Genetics of Bitter Taste

Further research has divided people into two groups: “tasters” who perceive PTC as bitter, and “non-tasters” who don’t detect any bitterness. The gene responsible for this ability is TAS2R38 (Taste receptor type 2 member 38), which encodes a bitterness receptor in humans. Its inheritance generally follows a Mendelian pattern, well known for dividing the genotypes into homozygous dominant (AA) or recessive (aa), and heterozygous (Aa).

Within the population, there are three main variations of the gene, named based on a one-letter codes for amino acids that build them. In European populations, the “taster” variation, called PAV, are almost equally common as the “non-taster” AVI variation, though this balance is different across the world. As shown by Dr Risso and colleagues at National Institute for Health, the non-taster variation is less common in Asian and African populations. Interestingly, about one in seven Africans carry a different variation, AAI, which is rare elsewhere.

Overall, the bitter taste receptor gene family turned out to be much broader in humans, consisting of as many as 25 functional genes and 11 “pseudogenes” (genes that ceased to be active over the course of evolution). Bitter molecules can bind to one, many, or none of the receptors they produce. For example, both absinthin and caffeine both bind to TAS2R member 46, curcumin to none and quinine (tonic water) to both 39 and 46.

Can All Animals Taste Bitter?

Not all the animals, nor even all vertebrates, have the TAS2 (taste receptor type 2) genes. Their size also varies, likely corresponding to the advancement of their bitter taste. It appears that they first appeared in fish during the Cambrian explosion. The timing suggests that it might have aided in animals becoming herbivorous. It’s supported by the correlation of the size of the receptors and the fraction of animal’s diet constituted by plants.

Although to me, it is more interesting which animals do not have any bitter-taste receptors. Among those are pinguins, some marine mammals (since they just swallow their pray whole). Snakes also have a narrow repertoire – my hypothesis would be that it’s for them not to taste their own venom.

Your Tastes are (Partially) Genetic

Next time you disagree with a friend on the taste of coffee, you can thank genetic variation for your differences. In summary:

- Tasting bitter is genetically determined.

- There are many receptors responsible for recognising specific bitter molecules.

- The variances in the receptors determine how sensitive one is to bitter taste.

Finally, if you’re curious, you can test whether you are a “taster” or “non-taster” – the PTC kits are broadly available for less than £5!

The Bitter Details

I am one of those people, that need to get to the core of things to accept them as a fact. Learning science can sometimes feel difficult for people like me, as different stages of biological knowledge use different levels of simplification. Here, I’d like to provide more details on the subject for any inquisitive minds that need it. I encourage you to read it and continue to ask questions.

- How different are the “bitter-tasting” genes?

Each variant distinguishes itself with just one amino acid. However, the differences occur at a different location within the structure, either close to the beginning or to the end.

- What does the receptor look like?

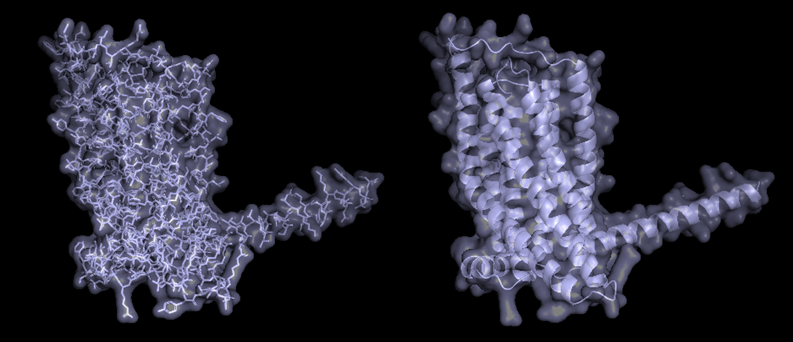

The T2R38 is a transmembrane receptor, meaning that it is located within the cell membrane. The inside of the membrane is made up of hydrophobic lipids (think: oil and water). That’s why the part of the protein that crosses the membrane is neatly lined with hydrophobic secondary structures called alpha-helices, that together create a pore.

- What does the “structural similarity” mean here?

Exactly what you think – when placed in a 3D space, an amino acid chain assumes a certain pose, which is difficult to predict. It is based on the interactions within the chain, their chemical structure and its environment. Proteins of similar shapes, especially receptors, might possibly bind the same molecules.

It is important to keep in mind that that position is not steady, but dynamic, and the prediction does not explain the behaviour of the protein in time.

- How much difference can one amino acid make?

Each amino acid has a different structure, taking more or less space in their environment. Similarly, a chemical they are binding (like the molecules responsible for bitter taste here), must fit the receptor in a certain way to be detected. Even a single amino acid change can obstruct their relationship.

Different amino acids not only have a different shape, but also interact differently with their environment. They can repel or attract other amino acids or their environment, thus causing a secondary change in the fold of the protein.

About the Author: Nina Wycech

Pronouns: she/her

I consider myself a collector of fun facts and interesting stories – which often come from science. I’m somewhat of a scientist myself. I graduated B.Sc. Neuroscience from UoM and I’m currently continuing my education at Glasgow doing an M.Sc. in Bioinformatics. My favourite subject is sleep & circadian rhythms, but I’ve been exploring genome sequencing extensively throughout my study.

Discover more from Research Hive

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.