Author: Zoe Chernova // Editor: Erin Pallott

“People think that stories are shaped by people. In fact, it’s the other way around.”

Terry Pratchett

Our whole lives are stories. We tell them to our children, read them in books, and can’t tear ourselves away from TV series precisely because we love stories. Our minds are built to want a narrative structure – to find meaning in the chaos of life. It’s our natural way of fighting entropy. Is there any storytelling in science? Well…

There were genius storytellers among scientists—Sapolsky, Feynman, Sagan—and their books and lectures are not only science but also great stories. There is also a Dance Your PhD contest—and it’s a great example of scientific storytelling! But in average science, there are almost no stories, and that’s something we can change.

Why does science need stories? After all, science is the language of facts, and they are quite convincing. The problem is that people still love stories and react to them – that is why those who engage in junk science and conspiracy theories win so much: their arguments are always stories. It is always about the son of a mother’s friend or the child of a school teacher of a colleague. Our brain reacts to these stories, processes them, and makes us think about them.

In scientific communication, there is rarely a hero and emotions. The author rarely includes themselves in their article or any other content, and their touch and personality are not felt. Science is based on facts, and facts rarely evoke emotions — but that doesn’t mean we can’t use them. The difference between scientific and not-so-scientific communication is that emotions only frame facts as a beautiful showcase. Yes, your story may be about the patient and his emotions, but the core of the story should be medical facts about the etiology of the disease, prevalence, and research. Emotions help us to understand: people outside of academia generally have a poor understanding of what science is, how science differs from an experiment, and what’s going on inside the labs. Including a story in your communication is a good way to introduce yourself and your science to the world. Storytelling helps us remember and understand more, increases ease of comprehension, and reduces reading time – it’s much easier to wade through the exciting story of Fredegund and Brunhild‘s relationship than to remember battle dates in the sixth century. The bridge between science and humanity is human emotions.

Storytelling can help not only when communicating with people outside academia but also with other scientists and colleagues. A study published in PLOS One found that writing style influences the citation levels. Storytelling can help you write about even the worst results!

So, we’ll talk about the general properties of science storytelling, its limitations and downsides, and then a little about specific tactics for creating different types of science content – from posters to presentations.

What is it?

Imagine you are reading a detective story. Most detective stories grab you from the first line: you can’t put it down and desperately want to read to the end, even if you suspect someone specific. A detective story is a good combination of tension and interest, and this is exactly what you can add to scientific storytelling. A good story typically has several main ingredients, a very clear structure that is also known as a “narrative arc”, and 3 types of arguments.

Let us start with the ingredients. Every story should have 5 Ws (who, what, when, where, why). To make it even easier, let’s focus on just 4 words: Hero (who), Conflict (what), Plot (when, where, what), and Emotions (why).

What does this have in common with science? Let’s start with the hero: it’s tempting to make a scientist your hero. But no, your hero is what you study: the blue whale, the wildcat, hemoglobin, or the Higgs boson. Even in your own research, you are not the main character – you need to determine who the hero is. The hero has a conflict – something happened or something is not right, and trying to solve the mystery makes the Plot. For example, you are trying to figure out which protein is responsible for a disease. It’s a kind of detective story: you have several suspects. Your protagonist is the patient, or rather, their clinical picture. One of the suspects causes this clinical picture (this is the conflict). You try to figure out who, going through protein after protein (this is the plot).

Finally, emotions. Just 3 words here: Make them care. The reader should constantly have a question: And then what? Or, even better: How does this relate to me? There are many jokes and stories, but many consider this not so important or even degrading to science. Emotions can be different; you need to understand which ones and what kind you want to evoke. Bitterness, pride, joy, laughter, inspiration, delight, or maybe sadness. What emotion do you want to evoke and why?

Now, about the narrative arc. You may know books like The Hero with a Thousand Faces by Joseph Campbell or Morphology of the Folktale by Vladimir Propp, which are all about narrative arcs. In fact, even a scientific article fits into Campbell’s hero’s journey! In short, we can use this arc:

old normal (background of your paper) — call (why you decided to do the study) — journey (you’re trying to figure out who your “suspect” is) — the goal (you know where to look) — struggle (results are terrible) — allies (new ideas have emerged or colleagues have helped you) — another struggle (lots of work in the lab) — new normal (you understand what’s going on and are ready to move on).

In Uniting science and stories: Perspectives on the value of storytelling for communicating science, you can find other shapes of scientific narratives: discovery, rescue, mystery – perhaps these arcs will suit you better.

There are also three types of arguments in a story. Science usually relies on Logos, which is the language of logic. There is Ethos, which is the language of reliability, facts, and authority. But there is also Pathos, which is the language of empathy, emotions, and “I care”. All three parts are important and help the story become whole, although they answer different questions: Logos answers the question “why?” Ethos “how exactly?” and Pathos – “so what?” A simple example: take the statement “cats began to meow more after domestication.” Why? “Because it is an easy way to attract attention” (logic). How? “Those cats that could tune a person to themselves and please them, survive and give birth to offspring” (facts). So what? “Now we love cats that actively respond to us and cannot refuse them anything” (emotion – love for cats).

You can also take a more “scientific” example. Imagine a grant application with the main idea “we need funding to create a new holographic anti-corrosion material”. Logos – this will bring the economy to the forefront, Ethos – this will help extend the life of equipment and reduce the cost of manufacturing machines, Pathos – this will help our planet, and we will produce less garbage, leaving our children a cleaner Earth.

Well, now you have a recipe for a science story. But there are also just a few important points.

1. Avoid jargon, abbreviations, and acronyms except for the most commonly used ones (obviously, you can use UK or the MSU abbreviation if you are a representative of the University of Michigan). There is even research that found that articles that contained a large proportion of jargon in their titles and abstracts were cited by other researchers much less often.

2. Avoid passive voice (the structure like “data was collected” or “experiment was conducted”). A story sounds much better when it has a narrator’s voice.

3. Understand your target audience and check the readability and complexity of the text.

There are downsides to scientific storytelling, or rather, aspects that are worth paying attention to.

- The use of narratives requires a careful balance between scientific accuracy and the goals of the target audience to avoid manipulation.

- Storytelling often requires simplifying information, which can lead to misinformation. This is especially problematic when narratives are used to explain complex scientific phenomena that directly affect people’s lives and health: for example, the issue of vaccination. Unfortunately, scientific literacy does not always lead to greater acceptance of science.

- As we have already discussed in the junk science topic, narratives are difficult to refute with facts, and sometimes the narrative and facts can contradict each other.

Articles and All Their Siblings

Let’s make it clear right away: a scientific article does not necessarily have to be a story. Its main purpose is different. Storytelling is just a tool, and it should be used wisely. You don’t have to try to make storytelling out of every article!

However, if you look closely, even an ordinary scientific article is already a story because the climax builds up to the results and then a kind of relaxation occurs – the results are explained in the discussion. There is even an epilogue in the form of conclusions.

But there are many siblings of a scientific article: from short stories for children and articles in popular science magazines to grant applications. What are the features of storytelling here?

- Hook: Start with something unusual, like a question or a “weird” fact.

- Background: Set the setting for your story. What was happening in the world before you started your research?

- History: Describe your scientific process. Arrange all the characters on the board: all the proteins, or particles, or stars, and yourself and your colleagues. List the methods you used.

- Problem: Your path was full of dangers, but you overcame them.

- Conclusions: During your journey, you came to such conclusions.

- Return and a new call: You have created a new reality in which you know a little more, but you already feel the next call.

Posters, Illustrative Materials and Infographics

Posters, visual abstracts, illustrations, infographics – all of these are great storytelling tools. However, they have limitations – most often, you, as a storyteller, will not be there, so they must work independently.

Each illustration and poster should have a main theme, which can be formulated as a takeaway note. Consider the goals of your audience: think about what your audience wants to receive. Are they looking for new research results? Are they interested in the practical application? Build an elevator pitch around this takeaway note – a short, well-written summary of your research. It is better to start drawing any illustration by hand, to sketch out different options. When the final version is already obvious to you, you can move on to PowerPoint (or any other tool).

Choose a story outline – for example, from the general to the specific (we looked at different proteins, but eventually settled on this one and studied it). Or vice versa – from the specific to the general (we looked at one protein but realized that there was a whole cascade of reactions there). The chosen color scheme also plays a role here – neutral sets the outline, and bright accents. Therefore, you should always have a primary color, one secondary color that accompanies the primary, and one bright accent color.

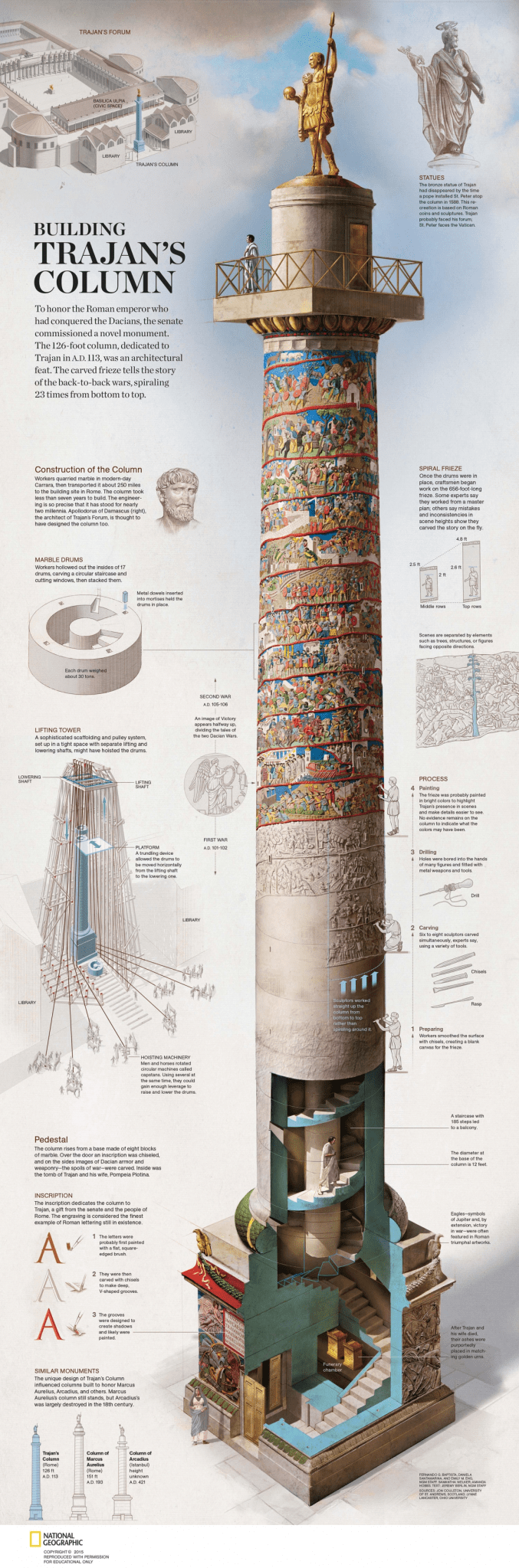

Let’s look at this infographic by National Geographic. The central column itself visually sets the pace of the storytelling. Our vision jumps around certain parts of the illustration, from top to bottom, exactly as the artist wanted to lead us. People like to follow columns (I’m sorry for the pun), even if there are no true columns and the text is separated by something. You also can use arrows, lines and other formats to navigate the readers.

The goal of each poster is to convey the depth and significance of the research without showing too much detail or complexity that could hinder accessibility. Avoid long paragraphs – resist the temptation to simply copy and paste the abstract into the top left corner. Instead, break up blocks of text into key points. In this case, using a bulleted list format can be too brief and usually does not fully utilize the canvas space. Instead, individual sentences can be a good compromise.

A good full guide to academic posters can be found here, and good examples of them here.

Presentations and Meetings

Finally, we have the presentation and all other speeches, from TED talks to conferences. The presentation is always supported by the narrator. The most important and catchy thing in a presentation is… the title! Therefore, the title should be extremely intriguing and memorable.

Presentations are often overly boring and full of tabular data and raw experiment results. Remember history lessons – dry numbers and facts are not history. Tell about the participants, their relationships and the events between them – and history will come alive.

The And – But – Therefore story arc is great for presentations, and they can be repeated within one story. For example, you describe a problem you had. Then you tell the solution and then the remaining problem. Repeat the cycle.

For example, let’s remember how PCR appeared:

Problem: Nobody understands how to make many copies of one gene.

Solution: We figured out how to add nucleotide sequences and polymerase.

Problem remains: Something works, but there is a lot of “noise” on phoresis.

Another solution: We figured out how to deal with this.

Still a problem: Great work, but we need to constantly change the temperature and add new polymerase.

Final solution: We added archaeal polymerase.

Eureka! We made a working PCR method.

This will help you create a good story around your research and present not dry data but the reality around the experiment.

Conclusion

Well, that’s my short guide to storytelling in science. We haven’t looked at “non-traditional” content here: for example, podcasts or video. But storytelling is also important there, for conducting a good interview or for telling a series of stories. In video, you can use visuals, combining history and visual storytelling. Storytelling will also help in education – including in science – and, of course, marketing. But that’s a completely different story (sorry for another pun!).

What to Read

The Tensions of Scientific Storytelling

Journalistic Practice: Science Storytelling

How to write a PhD in Biological Sciences: a guide for the uninitiated

How to deliver an engaging scientific poster presentation: Dos and Don’ts!

Building a Scientific Narrative

Telling Science Stories: Reporting, Crafting and Editing for Journalists and Scientists

About the author:

I’m Zoe, a science communicator and former researcher in the biochemistry department. Since leaving academia, I try to serve science in a different way: by telling stories. I am particularly interested in and write about modern medicine, women scientists, biochemistry, animal culture and cats. Outside of work, I also run a popular science newsletter, Look What I Found in Science.

Discover more from Research Hive

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.